Whether you are superintendent of a district, a principal, the dean of a teacher preparation program, or a state policymaker, there are likely a host of questions about the supply and demand of teachers that come readily to your mind. For example: Are vacancies caused by teachers leaving the district or are new positions being created? What are the retention rates of teachers of color compared to white teachers? How many physics teachers will graduate from the nearby teacher preparation program in the spring who might be interested in teaching in my school? Which teacher licensure area has the best placement success rate? We cannot answer these kinds of questions in a timely, accurate way, because states do not have the data. And because we do not have the data, we cannot create strategic and intentional policies to attract, recruit, and retain the most effective teachers, especially in our efforts to ensure educational equity and access.

Given this dearth of information, NCTQ set out to understand the key data elements states are currently collecting, which data is missing, and the level of detail that is needed to meaningfully answer questions about the teacher workforce. This work expands on a previous report that focused on the teacher supply and demand data states make public, which revealed serious gaps in the public availability of data. In July 2022, NCTQ surveyed states to determine the extent to which they collect data on 39 distinct data elements related to teacher supply, demand, and demographics. We looked at three aspects of the data:

- Organization: Availability of the data at the state, district and school level (demand); or institution of higher education and teacher preparation program (supply).

- Subject-area: Availability of the data disaggregated by certification area (supply) or subject area (demand).

- Timing: Availability of the data for the school year that had just ended at the time of the survey (2021-2022) or the prior year (2020-2021).

- Health of the teacher pipeline

- Teacher turnover (attrition), mobility, and shortages

- Equitable assignment of teachers

[health]

Do we have enough new teachers coming into the profession to fill available positions?

To answer this question, we need not only an overall headcount of new teachers, but also the numbers by licensure or certification area to compare to the demand for teachers by subject area.688 We also need this information by geographic location: For example, how many teachers graduated from teacher preparation programs that serve different regions of a state, such as urban centers or rural regions? Are there "teacher deserts" with no teacher production near districts with an unmet demand for teachers? How much of the teacher supply is comprised of teachers certified in other states, or those re-entering the workforce?

Understanding the numbers of teacher preparation program completers is just the beginning of assessing the health of the teacher pipeline. Little is still known about whether these teachers are actually hired as teachers of record. In order to answer these key questions, data needs to be linked from higher education data systems both to teacher licensure systems and to K-12 data systems, so states and districts can learn more about their teacher supply. This would provide insight into where their teachers come from, how many actually enter the classroom, and what gaps exist and where. These links would also help hold teacher preparation programs accountable not only for producing graduates, but also for their ability to prepare teachers to enter the workforce and be successful with students.

All of the 43 states that responded to our survey told us they have data that allows them to identify the number of newly credentialed teachers produced every year. But only 66% (29 states) said they could tie teachers currently employed in a public K-12 school with the certifying institution from which they graduated. Even fewer (25 states or 58%) can link teachers to the specific teacher preparation program within that institution. And less than half of the states reported being able to link teachers who are certified but not currently employed to the institution that prepared them.

[attrition]

Which teachers are leaving or moving jobs, and where do shortages exist?

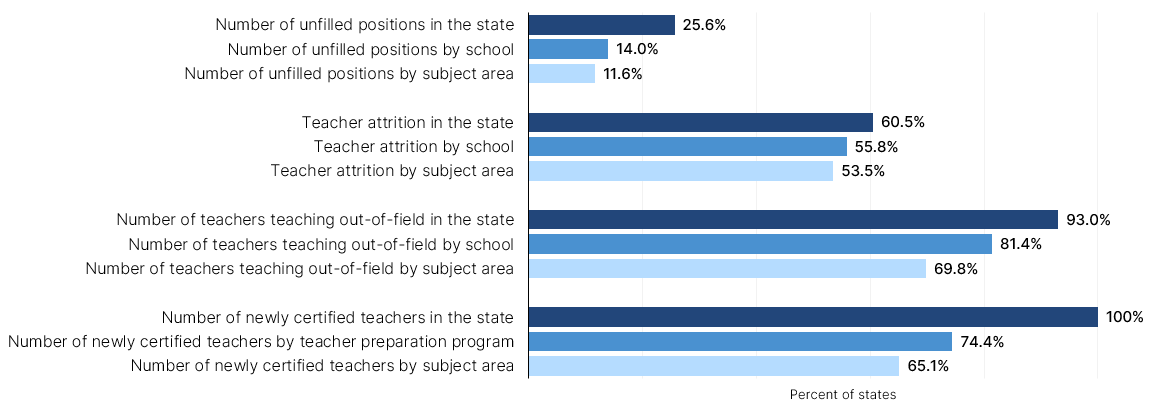

Twenty-seven state respondents (over 60%) report they have data on most of the elements that could inform questions about teacher shortages. Almost all states that reported having the data also reported having it for the current school year, even if not publicly reported. However, less than half report having this data disaggregated by subject, meaning that fewer than half of the states can tell us which subjects have shortages and which are experiencing surpluses. Said otherwise, most states and districts do not know whether they have secondary math teachers or elementary teachers leaving their positions; or whether teacher preparation programs are going to be sending them physics teachers or PE teachers.

While more than half of the states report having data on their current teachers in the workforce, only 11 states (about a fourth of our respondents or less, depending on the disaggregation level) have data on teaching positions. Their data systems track people, not positions. The absence of this specific data limits the ability to get a clear idea of the actual demand for teachers, since the demand for fully certified teachers is caused by:

- Teacher attrition,

- Teachers teaching out of field or not fully certified, and

- New teaching positions due to growth in student enrollment, additional student needs, or class size limits.

Figure 1.

Availability of disaggregated data to inform teacher shortages

[equity]

Which students are getting access to which teachers, and does teacher assignment promote equity or reinforce teacher quality access gaps?

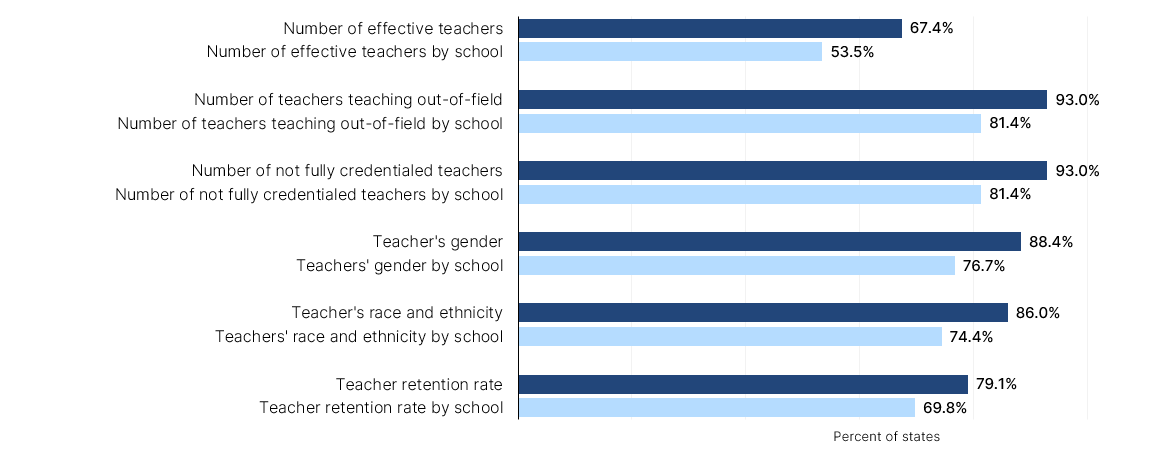

Most states report having available data on teacher characteristics, such as gender, race, or years of experience. However, it is somewhat less common to have this data disaggregated by school. As reported by survey respondents, demographic information of teachers is widely available—about 36 states report having different demographic data elements on their teachers—and only slightly less do so by school (available in about 32 states689).

Information on teacher effectiveness (as defined by the state) is the least available of teacher characteristics—28 states report this measure at the state level and 22 do so at the school level—perhaps one of the most relevant data elements to promote equity in student learning.

Availability of data on characteristics of the teacher workforce by school

[recs]

Next steps for state education leaders

Most states report they have data systems that generally account for their teacher workforce, and therefore can generally describe their workforce characteristics. Fewer states, however, have this data disaggregated in a way that allows them to answer the most important questions about their teacher workforce. Data connections between the teacher workforce and teacher preparation programs are even more rare. What can states do to improve their data and consequently improve the policies that would help them build a more diverse and effective teacher workforce?

- Identify the key questions your state needs to answer and when. For these systems to be useful in building a diverse and effective teacher workforce, the state needs to be able to first identify the specific questions they seek to answer, and then pinpoint the data needed to answer them. NCTQ created this document to help guide states in this exercise. States also need an idea of when those key questions need to be answered, as some of the staffing challenges highlighted by their questions call for proactive rather than reactive solutions. Identifying when specific data is needed can support states to develop creative solutions, such as forecasting staffing needs or designing data systems that provide real-time reporting on teacher vacancies.

- Enact policy to collect the key data elements needed to understand your teacher labor market. While most states have some of the needed data available, this survey demonstrates that there are key pieces of information and connections still missing. States should consider enacting policies that enable the collection of the missing data, such as legislation or regulation. A recent statute enables Colorado to collect data on teaching positions; it calls for this data collection to identify the specific subject areas, grade levels, and geographic areas of the state in which teacher shortages exist or are likely to exist within five years. With the authority to collect this data, the state now produces a dashboard to help districts and policymakers understand current teacher staffing needs and how vacant positions are being filled.

Another approach to collecting teacher demand data is the one developed by Indiana. The state is currently investing in a statewide educator recruitment portal, with at least 50% of districts initially participating on a voluntary basis. Alongside the benefits of a centralized source of information on teaching jobs, this portal also generates data on open positions and district staffing needs in real time. - Invest in state data systems that focus on teacher supply and demand, with the appropriate links along the whole teacher pipeline. Over the last ten years, states have made significant investments in student data systems, and rightfully so. Now is the time to make similar investments in teacher workforce data systems. Establishing a unique identifier for individuals in teacher preparation programs and continuing the use of that identifier into the K-12 teacher employment system provides the data that allows states to study teacher workforce patterns more in-depth, from pre-service to in-service.

In Tennessee, available data connections between teacher preparation and teachers in the workforce allows the state to produce the Tennessee Educator Preparation Report Card, which assesses the performance of the teacher preparation program from recruitment of teacher candidates to graduation, employment, retention, and assessment of teachers in the classroom, including measures of how teachers feel their preparation program prepared them for teaching.

If you are interested in improving the teacher workforce data systems in your state, the National Council on Teacher Quality (NCTQ) is available to provide technical assistance and collaboration. Contact Dr. Patricia Saenz-Armstrong at psaenzarmstrong@nctq.org for more information.

[ack]

Authors

Dr. Patricia Saenz-Armstrong

Shannon Holston

Dr. Heather Peske

Reviewers

Special thanks to the following individuals for providing review and feedback on this project. Inclusion does not imply endorsement.

Dr. Dan Goldhaber

Director, Center for Analysis of Longitudinal Data in Education Research (CALDER) and Center for Education Data & Research (CEDR), University of Washington

Dr. Mark Olofson

Director of Educator Data, Research, and Strategy, Texas Education Agency

Brennan McMahon Parton

Vice President, Data Quality Campaign (DQC)

Project funder

This report is based on research funded by the Walton Family Foundation. The findings and conclusions contained within are those of the authors and do not necessarily reflect positions or policies of the project funder.

[endnotes]

Endnotes