Much like other kinds of tests found in schools, teacher licensing tests have fallen out of favor. It's rather remarkable, their quick fall from grace. Less than a decade ago there was a groundswell of support for raising the academic bar for who gets into the profession, intent on mirroring the much higher entry standards of other nations (remember Finland?). While licensing tests were then characterized as a milestone to achieve, now they're regarded as an obstacle to be removed.

Just look at what has happened recently to basic skills tests. In 2015, there were 25 states that required anyone trying to get admitted into a teacher prep program to pass a test in reading, writing, and the mathematics associated with the job of teaching. Five years later, our data shows that number has dropped to 15—the legislative equivalent of a tidal wave—with tests in many of the remaining states hanging by a thread.

Based upon what I'm hearing, there appear to be three primary rationales for reducing or eliminating licensing tests:

- the tests are biased, due to the fact that much higher percentages of Black and Hispanic candidates fail the test than white candidates;

- the tests don't predict whether a teacher will be effective, so why require them; and,

- there's an urgent need to diversify the profession that should take priority over any other considerations, given the profound benefits of matching teacher and student race.

If true, each of those alone provides a compelling argument to lessen the weight of licensing tests. Considered as a group, it is no wonder the future of the tests is teetering on the edge.

The problem for me (and plenty of others, I imagine) is that not one of the three is unequivocally, demonstrably true. In the laudable, appropriate pursuit of a more diverse workforce, it's tempting to overlook the shaky ground on which some of these rationales rests, that the rightness of this cause is so great that the risks are worth it. And by risks, I refer to deep harm to teacher quality from allowing underprepared teachers into the classroom, something we can ill afford to inflict on children whose lives depend on their access to great teachers.

Are licensing tests biased?

Consider first the issue of testing bias. The fact that a particular demographic group scores lower on a test does not meet the legal definition of bias. What is needed to prove bias is evidence that a group or class of people fail a test despite having equivalent content knowledge as those who passed the test. It also has to be proven that the content knowledge in question is irrelevant to the demands of the job. To my knowledge, no such evidence exists for any of the teacher licensing tests currently in use, while there is plenty of hearsay.

Systemic inequities in K12 education are far more likely to be the cause of high failure rates. There is, unfortunately, all too much evidence that our nation's K-12 schools have deprived many prospective teacher candidates (no matter what their color, but certainly candidates of color are disproportionately harmed) of some fairly basic knowledge and skills that the teaching profession demands. There is also considerable evidence that the approach taken by the nation's teacher preparation programs to better prepare candidates for licensure has fallen short. Still, I recognize that it is far easier to shoot the messenger here than to hold our schools and higher ed institutions accountable for doing their jobs.

Do licensing tests measure what matters?

Issues of bias aside, what if these tests are measuring content knowledge that doesn't matter? This seems to be the most common of the three arguments against licensing tests. I've heard many testimonials from people who run schools describing teachers who turned out to be fabulous but who hadn't been able to pass their licensing tests.

There's no reason to reject the accuracy of these testimonials, but neither should they be the basis for getting rid of licensing tests. For starters, no single test can measure everything that makes a teacher effective (nor are tests all that good at measuring important 'soft' attributes). But tests are the most efficient and effective way to measure something like content knowledge—which all teachers need to have regardless of what other attributes they bring to the table.

There is no system used to screen people, be it for medical, legal, or educational purposes, that is 100% accurate. There will always be false negatives (e.g. COVID-19 tests). It's also the case that the structure of many teacher licensing tests creates an unusually high number of false negatives, as they tend to cover a large span of grades, most notably K-5. No doubt a 1st grade teacher does not need the science content that a 5th grade teacher does, though in many states both fall under the same certificate—and the same test.

The research to date comes down mostly on the side of licensing tests, suggesting that the academic skills and content knowledge needed to do well on at least some of them is relevant (I would argue not surprisingly) to the demands of teaching. There are a lot of different licensing tests out there, most of which have not been studied. However, the high number of tests speaks more to states holding on to the illusion that they must have their 'own' tests than it does to their actual variability. Apart from performance assessments, they mostly test for three things: basic skills, how to teach reading, and knowledge of a subject area.

New research puts this issue into perspective

Consider this important new paper from University of Washington economist Dan Goldhaber and his colleagues James Cowan, Zeyu Ji, and Roddy Theobald. They find that licensing tests used by Massachusetts clearly and without regard to the color of a teacher predict the effectiveness of a future teacher. Examining that state's version of a basic skills test along with its subject specialization test, higher scoring candidates consistently produced higher value-added scores in the classroom and earned higher evaluation ratings. The relationship was neither small nor nonlinear. New teachers who did well (greater than or equal to 1.0 standard deviations) on the Massachusetts tests cut in half the learning loss students generally experience under the average first-year teacher, in effect suggesting that school districts can erase much of the decline in learning that occurs in first-year teachers' classrooms just by hiring smarter.

It's worth mentioning that Goldhaber with his colleague Michael Hansen conducted a similar study of North Carolina teachers in 2010, finding that the licensing test in that state, while reasonably sound overall, was not as predictive across teachers of different races or ethnicities. Performance on the North Carolina test did predict future teacher effectiveness, but underestimated the future effectiveness of Black teachers—an important reminder that states use different tests and different levels of bias screening, among many other factors. Some tests are better than others, a fact that should spur improvement, not abandonment, of an essential tool for ensuring teacher quality.

Diversity and quality are not mutually exclusive

The last of the three rationales addresses the benefits provided to kids of color when they experience as few as one teacher of the same race or ethnicity. The positive benefits to students from experiencing a teacher that looks like them are genuinely exciting and give us new hope for ameliorating the inequities of our education system. Diversity is a critical component of a high quality workforce and is a core value at NCTQ. However, this research does not support policy actions to undo all academic standards. The teachers of color in these studies presumably for the most part met the academic standards of their state. To my knowledge, there is no study that indicates that the only attribute that matters about an effective teacher of color is the fact that they are of color.

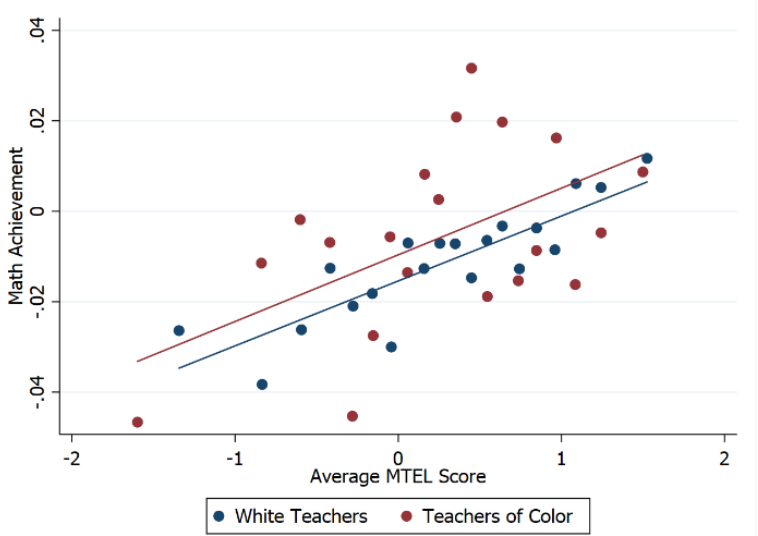

Returning to Goldhaber's Massachusetts findings, this fascinating chart shows that not only do the licensing tests predict future teacher effectiveness, but the relationship between Black and Hispanic teachers who did well on the licensing tests and their students' math performance is actually stronger than for white teachers. In fact, some of the Black teachers represented here were responsible for the 'outlier' level of performance (perhaps some more evidence of the importance of diversity?).

The relationship between teacher performance on licensing tests (MTEL) and their students' math achievement

From: Cowan, J., Goldhaber, D., Jin, Z., & Theobald, R. (2020). Teacher Licensure Tests: Barrier or Predictive Tool?. CALDER Working Paper No. 245-1020.

With all the energy and enthusiasm for achieving a more diverse workforce, it's been dispiriting to see states and advocates turn to strategies that not only put teacher quality at risk but are, frankly, counterproductive. By removing all barriers (such as licensing tests) in response either to teacher shortages or the need for greater diversity, we are actually just switching out one kind of barrier for another. This new barrier signals teaching as a "last resort major" and a low status career. The trend underway to make the teaching profession easier to get into than almost any other profession does not play well with talented college students who have lots of options and are in high-demand from all sorts of employers. That's especially true for talented persons of color.

While much of the nation seems determined to ignore science and restrict their worldview to what their friends say on Facebook, we can do better here. We can do a lot to increase the diversity of the teacher workforce by holding schools and teacher preparation programs accountable. That's not the simple answer some might seek, but it is the right one.