A new study casts some legitimate doubts about just how much of a cash cow ed schools really are.

A new NBER working paper analyzes data collected by the long running Delaware Cost Study (DCS)—a misleading name on a couple of fronts, in that it is more of a database than a study and it collects national data, not just information on Delaware. For the most part, DCS focuses on the costs of various functions in higher education, including instruction and research.

In "Why is math cheaper than English? Understanding cost differences in higher education," Steven Helmelt (University of North Carolina, Chapel Hill) and colleagues provide a first-of-a-kind public glimpse into the costs of educating students in various academic disciplines. Believe it or not, campus colleges of education (which include the teaching major, among other specializations) stand out for having some of lowest class sizes—presumably leading to their next finding that colleges of education post some of the highest instructional costs. Since 2000, teacher education has experienced dramatic increases in costs along with similarly large decreases in class size. The following charts show how education stacks up against other disciplines included in the study.

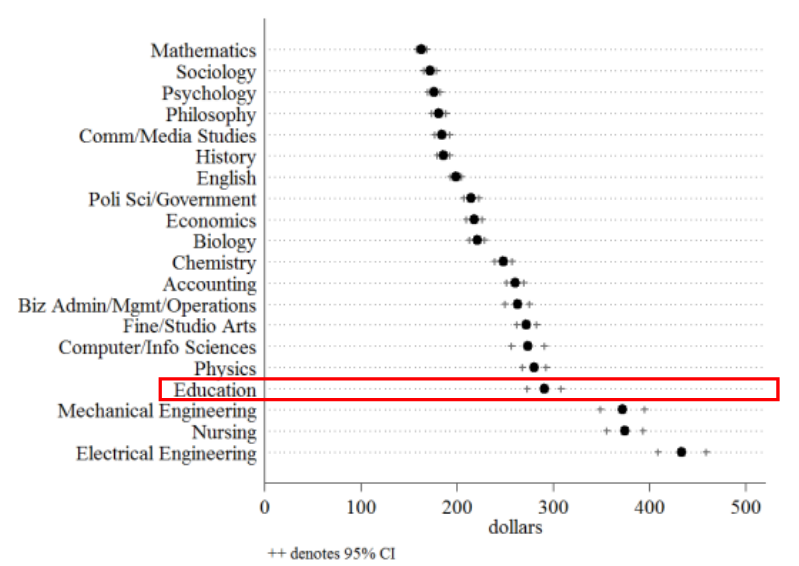

Average Instructional Cost (Per Credit Hour)

Education courses cost nearly $300 per credit hour to provide—exceeded only by the costs of courses in engineering and nursing.

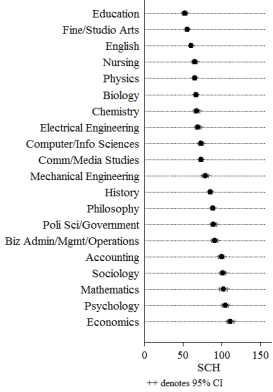

Further, courses in the colleges of education have average class sizes smaller than any other department on a campus. In this study, class size is represented by the total credit hours earned by all of the students enrolled in a course section. A three credit course with 20 students enrolled in it would have a value to the university of 60 credit hours.

Total Credits Earned by All Students Enrolled in a Course Section (used as proxy for class size)

There are lots of lingering questions here about the data, as we only see averages, not the spectrum of costs which surely vary for programs of different sizes or disciplines. Nevertheless, the study certainly calls into question the popular cry that education is higher ed's greatest cash cow.

What's also evident is that many academic departments are able to bring down their costs by providing courses to non-majors, such as requirements that all campus freshmen have to take an English lit or math course. Our general knowledge of how college requirements work tells us that education departments are less likely to offer courses for general ed requirements than are liberal arts departments. This study now helps quantify how that difference impacts operational costs.

It also potentially argues for shifting some of courses outside ed departments, such as psychology courses, which are often the domain of education departments, in order to gain a broader appeal. Enough with the "Biology for Teachers" courses—let everyone learn the good stuff from the subject matter experts to improve program quality and costs.