Paying teachers more to work in high-need schools and subjects—known as “differential pay”—is one of the most powerful tools school districts have on hand to secure the teachers they need.

While offering a higher salary for positions in high-need schools and subjects is most compelling, it is not the only differential pay action available. A review of a sample of districts and all 50 states plus D.C. shows that some entrepreneurial education leaders have adopted creative differential pay policies, offering incentives that range from up to a $20,000 bonus in D.C. for teaching in a high-needs school to mortgage assistance for teachers in both high-need schools and subjects in Connecticut.

In working to adopt and implement differential pay policies, both districts and states should look to these examples from their peers.

For brevity’s sake, we use the term “pay” to encompass all forms of additional compensation, including one-time bonus payments, annual salary supplements (sometimes referred to as stipends), increases in base salary, loan-forgiveness, mortgage assistance, and tuition reimbursement.

How are districts using pay as an incentive?

A review of the 100 biggest school districts in the country along with the biggest district in each state (for a total of 123 districts) shows that two out of three districts have some sort of policy that supports additional pay for teachers in high-need schools or of high-need subjects. In the chart below, you can see how many districts have which types of policies.

The results are surprising. The districts in this sample are nearly twice as likely to have policies to pay teachers more to teach high-need subjects, such as STEM, ESL, and special education, than to pay teachers more to work in high-need schools.

For both high-need schools and subjects, the most common way that districts provide additional pay is through an annual supplement rather than by raising teachers’ salaries. Because these supplements can be renewed each year, they are different than a one-time bonus, which is typically a signing bonus for a teacher new to a school or district. (Of course districts will often pay a bonus for improving student achievement, but that belongs in the category of performance pay.)

Although no district has a separate salary schedule or increased salary steps for teachers in high-need schools, 15 do for high-need subjects. For example, in Anne Arundel County (MD), new teachers in high-need subject areas can earn up to five years of additional experience credit on the salary schedule, and in Atlanta Public Schools, Kanawha County (WV), and Wake County (NC) special education teachers, almost always in short supply, are paid on a separate, higher salary schedule.

A handful of districts employ multiple strategies. Jefferson County (KY) policy gives a one-time bonus to teachers with a three-year commitment to teach in a high-need school and goes further to offer teachers in high-need schools tuition reimbursement to pursue an MA degree, child care subsidies, and additional school-wide bonuses based on student achievement.

Some districts leave it up to the superintendent’s discretion. Charlotte-Mecklenburg Schools (NC) and Elk Grove Unified (CA) allow superintendents to offer bonuses, stipends, or other incentives to teachers in certain schools. In Newark (NJ), superintendents can offer a $3,000 or $4,000 bonus and grant teachers advanced standing on the salary schedule if they can teach a high-need subject.

How are states using pay as an incentive?

Among all 50 states and the District of Columbia, 35 have some policy regarding differential pay, leaving 16 with none. These include incentives such as loan forgiveness, mortgage assistance, and additional pay in the form of stipends or bonuses or salary awards.

Interestingly, states are more likely than districts to have policies encouraging teachers to work in high-need schools but less likely to have policies for teachers of high-need subjects. Specifically, 32 states maintain a differential pay policy for high-need schools, but only 28 states maintain such a policy for high-need subjects. States’ policies reflect an emphasis on ensuring teacher equity across schools.

Are districts on the same page as their states?

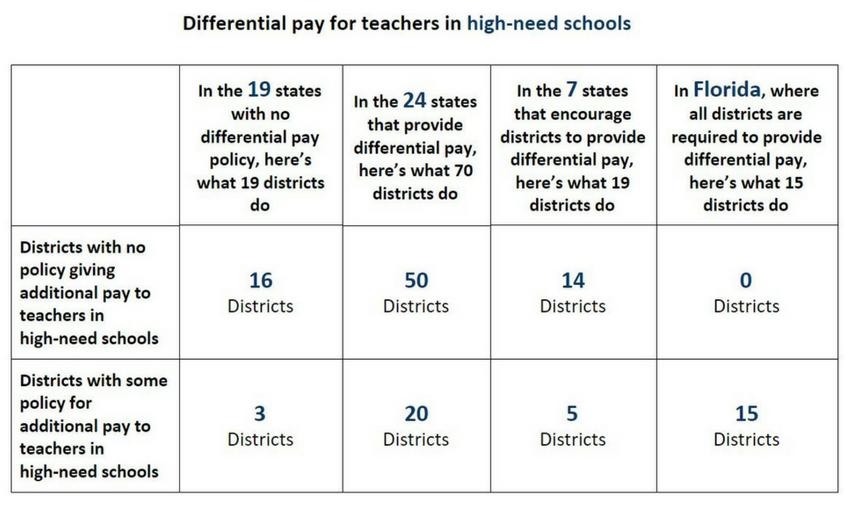

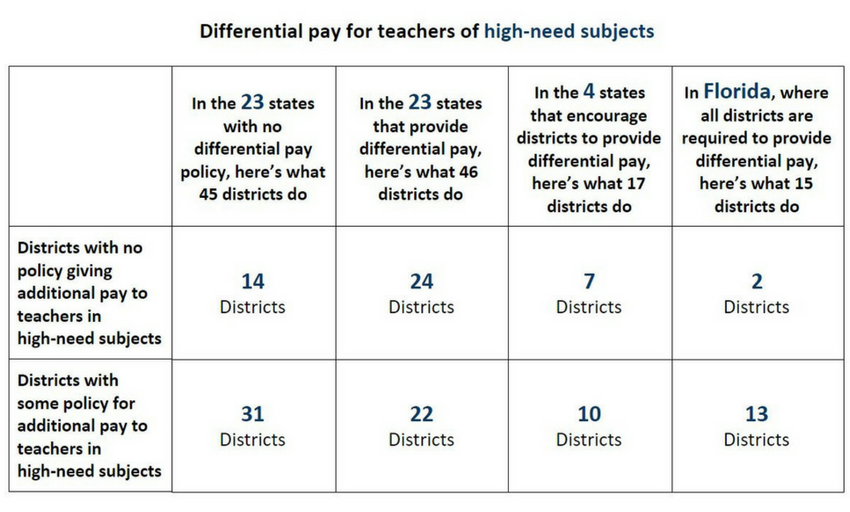

By grouping the 123 districts in the sample according to state differential pay policies, you can begin to see the relationship between state1 and district pay policies. (Note: Given the small district sample size, many states have only one district in the sample. These data are not generalizable to any one state, but provide a snapshot of this work.)

Only three of the 19 districts located in states with no differential pay policy for teachers in high-need schools have implemented a policy of their own volition. In contrast, when the state provides some additional pay policy for teachers in high-need schools, many more districts—but still fewer than half—add additional differential pay policies on top of what states offer.

While 20 districts supplement their state’s differential pay policies for teachers in high-needs schools, six of these districts only offer this supplement in very limited circumstances. For example, Aldine and Klein Independent School Districts in Texas only offer this additional pay to teachers in certain alternative education positions, while Dallas and Fort Bend Independent School Districts, also in Texas, offer additional pay for teachers that meet certain criteria and who teach in schools participating in a district-led innovation program.

In the seven states that encourage districts to offer differential pay for teachers in high-need schools, only five of the 19 districts in our sample do so, perhaps reflecting a divergence of state and district priorities.

Although the results are only suggestive given the small sample size, it is interesting to note that even when states do not have policies that support additional pay for being able to teach a high-need subject, two-thirds of districts in our sample have such policies. Alternatively, when states articulate a policy, about half of districts add their own policies. For example, Colorado does not have a state policy for additional pay for teachers of high-need subjects, but all four Colorado districts in this analysis—Cherry Creek, Denver, Douglas County, and Jeffco Public Schools—have policies that enable differential pay for in-demand teachers.

Florida has its own column because of its state requirement that districts provide differential pay to all teachers in high-need schools and subjects. About two-thirds of the 15 Florida districts in the sample give an annual supplement to teachers, while one-third give a one-time bonus. Appearing to be in conflict with the law, neither Pinellas County nor Seminole County school districts have differential pay policies articulated for teachers of high-need subjects.

Don’t forget implementation!

After adopting a differential pay policy, states and districts must make sure the policy is properly funded and implemented so that the targeted groups of teachers receive the compensation. Districts can have strong policies but fail to take the necessary next-steps, as in the example of Cleveland. States must also ensure that districts are implementing any mandated policies with fidelity—an issue with Florida’s performance pay law—and, of course, state legislatures must secure the funding needed to make sure policies can be effective.

Differential pay policies for high-need schools and subjects should be a key part of recruiting and retaining teacher talent. Both states and districts have important roles to play. Moving forward, the big research questions that come out of this work revolve around how district and state policy intersect as well as how entities can best promote successful implementation of differential pay. The students in those high-need subjects and schools deserve nothing less.

For more on differential teacher pay, check out these resources:

NCTQ’s Strategic Compensation Databurst– an analysis of how states approach teacher pay along with recommendations for using pay strategically.

The January 2018 District Trendline on performance pay and its use in large districts.

The May 2017 District Trendline analysis– how districts define high-need schools and subjects and what the additional pay looks like.

More like this

More districts are paying teachers strategically to meet critical needs. Is yours?

Transforming education: The LEARNS Act’s impact on teacher salaries in Arkansas

Building a strong student teaching model: Districts and teacher prep programs share successes and challenges

Coming up ACEs in Dallas: Differentiated pay for teachers and dramatic gains for students

Endnotes

- For this analysis, the 24 states that provide differential pay are defined as those that allocate state funding for teacher bonuses, stipends, loan-forgiveness, or other forms of compensation. The seven states that encourage districts to provide differential pay are those that definitively state that districts may dedicate resources to provide additional compensation to teachers in high-need schools or high-need subjects.