Priced out: The growing challenge of teacher pay and housing costs

A new NCTQ analysis finds that despite salary increases since 2019, teachers are falling further behind in the race for housing affordability.

Learn more about evidence-based approaches to strengthening and diversifying your teacher workforce with NCTQ’s reports, guides, and articles.

A new NCTQ analysis finds that despite salary increases since 2019, teachers are falling further behind in the race for housing affordability.

May 8, 2025

Katherine Bowser

Math skills are critical for students’ success in other subjects and later in life, yet far too many teacher prep programs fail to give aspiring teachers the essential knowledge they need to be effective math teachers—undermining student learning before the first lesson even begins.

April 8, 2025

Graham Drake, Ron Noble, Heather Peske

Nationally, the diversification of the teacher workforce is slowing compared to the diversification of college-educated adults, but California, Texas, and Washington, D.C. are bucking that trend. Explore what factors contribute to their relatively high rates of teacher diversity and how their policies and practices will likely affect teacher quality.

February 1, 2025

Ron Noble

Without first understanding a problem, it’s next-to-impossible to fix it. A new policy brief demonstrates how one state looked first to data to better understand its schools’ inequitable assignment of teacher talent, surfacing some issues that were largely unknown.

April 19, 2018

Nick Ledyard

About 20 school districts have adopted new staffing models known collectively as Opportunity Culture, each designed to maximize the impact of great teachers. Makes sense, but does it work? Thanks to a recent study from Ben Backes and Michael Hansen, the first bit of evidence is in.

April 19, 2018

Kency Nittler

As many states struggle to staff all their classrooms, they might want to examine the degree to which their own policies discourage qualified teachers from applying.

February 15, 2018

Catherine Worth

Considerations from NCTQ

February 1, 2018

Hannah Putman, Nick Ledyard

Even today, high-needs schools struggle to attract and, more critically, retain effective and experienced teachers. We think teacher prep programs are missing a huge opportunity to tackle this issue, through student teaching placements.

January 25, 2018

Nicole Gerber

There is a cautionary lesson from a new working paper examining Houston’s bold talent initiative. In many ways, it yielded the results intended by retaining a higher number of great teachers and exiting weak ones. It also led to a few unintended and unwelcome outcomes.

January 18, 2018

Hannah Putman

Permit me to draw my inspiration from scripture, referencing the basic human needs of clothes on our backs, food to eat, and a shelter over our heads. How better to discern if in fact teacher salaries are where they need to be? Applying salary data from our Teacher Contract Database, we asked this question: are teachers paid enough to put a roof over their heads?

October 19, 2017

Kate Walsh

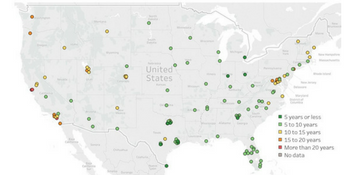

Despite how some organizations tend to discuss teacher supply, the United States doesn’t have just one teacher labor market, but at least 50. Why is the labor market so fragmented? Each state creates its own teacher licensure policies and none of them employ a practical approach to licensure reciprocity. The result is a complex and expensive process for teachers who want to teach in another state. Couple this obstacle with inflexible pension systems and, voila, each state has its own labor market.

In that vein, a group of economists at the University of Missouri set out to learn how these ‘walls’ between states impact student achievement. To investigate, Dongwoo Kim, Cory Koedel, Shawn Ni, and Michael Podgursky devised a clever study comparing student achievement at schools that are within a few miles of a state border to schools that are not near state borders.

Why would that be telling? We know from previous research that teachers like to work close to where they live, so if various state policies make it difficult for teachers to move across state lines, those schools close to state lines would in theory have a smaller pool of teachers from which to recruit. This, in turn, might decrease teacher quality in those schools.

The results of this study prove the hypothesis correct. Using a 10-mile radius as each school’s prime hiring market, the researchers determined that in schools where at least 25 percent of the potential teacher workforce lived across state lines, 8th grade math achievement was lower compared to that in schools that had access to all of the potential teacher workforce within 10 miles.

The authors note that although the effect is relatively small, there are over 600 schools that reside near state borders, thereby impacting the achievement levels of 670,000 students across the country.

One can imagine that in places like Dakota Valley School District, bordered by districts in Nebraska and Iowa, easier licensure reciprocity could be a big boon to teacher recruitment efforts.

One step states can take to ensure that students near the border don’t miss out on the best teachers is to offer a standard teaching license to certified teachers from out of state–taking some of the border walls down.

October 19, 2017

Kency Nittler

Teacher salaries are always in the news, but in the last few months we’ve noticed that housing affordability for teachers is in the spotlight, with many school districts exploring ways to support teachers’ ability to rent or purchase homes. This month, we assess the ability of teachers to: 1) rent an apartment, 2) save for a down payment, and 3) make a monthly house payment.

October 17, 2017

Kency Nittler

Like all of us, principals respond to performance pressures by seeking to alleviate them as quickly and simply as possible. Unfortunately, when it comes to the pressure to improve test scores, the simplest solution may be the most likely to backfire.

A recent study by Jason Grissom of Vanderbilt University and Demetra Kalogrides and Susanna Loeb of Stanford University shows that over a ten-year period, principals in Miami-Dade County Public Schools rearranged their teaching staffs in response to the accountability pressures of No Child Left Behind. Principals moved their best teachers into tested grades (3rd through 10th), presumably with the goal of improving outcomes in the grades most obviously linked to schools’ accountability scores.

The researchers found that principals were more likely to engage in this type of “strategic staffing” in schools where they had more control over staff assignment and in schools that had received a failing grade and were therefore facing particularly intense pressure to improve. Overall, a below-average teacher (with student assessment scores one standard deviation below the mean) had a 13 percent chance of being moved to a non-tested grade, compared to a 5 percent chance of being moved among above-average teachers.

Of course, moving a struggling teacher to a different grade would not be bad IF that teacher turns out to be better equipped to teach that new age range. A non-state assessment administered by researchers to gauge performance in the earliest grades revealed this not to be the case; instead, they found that K-2 students taught by teachers who had been moved from a higher grade lost so much ground that it carried over into their performance on the 3rd grade tests, if not even longer.

What seems like a sound short-term strategy actually creates longer-term harm.

September 14, 2017

Hannah Jarmolowski

Should schools of education steer their students to fields where they have the highest chances of being hired? Or should they allow students to major in fields in which the college knows only a few will eventually find jobs?

September 1, 2017

Sam Lubell

Every year, shifts in school enrollment,

programs, or other factors require schools to transfer some teachers out of their

current position at a school. But how do those teachers find a new position — and

what happens to the teachers who can’t?

August 3, 2017

Kency Nittler, Hannah Jarmolowski

There has been substantial media attention recently regarding states’ Every Student Succeeds Act (ESSA) plans, much of which has focused on states’ efforts to meet ESSA’s accountability requirements. Here at NCTQ, we took a close look at another aspect of ESSA, by analyzing states’ plans to meet ESSA’s educator equity requirements.

Last month we released educator equity analyses of the 16 states and the District of Columbia that submitted their plans in spring 2017. Our analyses highlight strengths and opportunities among these states’ work to ensure that low-income students and students of color are not disproportionately taught by ineffective, out-of-field, or inexperienced teachers.

Criticizing states or highlighting failings in these plans are not the goals of these analyses. Instead, we showcase states with strong elements worthy of replication and mention opportunities for these plans to be enhanced.

Of course, equity issues extend beyond districts and schools. Indeed, many of these issues have their roots in our shameful national history of housing and hiring discrimination, racism, and classism. Nevertheless, states have a critically important role to play in ensuring that, regardless of the cause, where educator equity gaps exist, states, districts, and schools must work to eliminate them.

Since research clearly demonstrates that a teacher is the most significant in-school influence on student achievement, states, districts, and schools must provide effective teachers with incentives and support to serve where they are most needed: in our highest need schools. States and districts should take actions designed to ensure that more of our best teachers are teaching in classrooms where they can help our most at-risk students.

Overall, our review of state’s efforts to meet the educator equity provisions in ESSA state plans found that some promising work is underway, but also that significant room for improvement remains. Specifically, we found that the best plans contain the following elements:

Our analysis found that many ESSA state plans include strong definitions for an ineffective teacher that include objective measures of student growth. However, many states have substantial room for improvement in establishing ambitious and achievable timelines and interim targets for eliminating existing educator equity gaps.

Failing to ensure that low-income students and students of color have equal access to excellent teachers robs them of a vitally-needed chance to succeed. Fortunately, states have powerful levers that they can use to close equity gaps.

For example, when designing strategies intended to eliminate educator equity gaps, states should engage with the full range of policymakers who will be responsible for implementing these plans. States also should carefully review whether districts with longstanding equity issues are using state and federal education funds strategically to address any existing educator equity gaps.

Additionally, states can and should take steps to ensure that progress toward eliminating equity gaps is regularly measured. States should also implement processes for evaluating and improving the strategies that districts are implementing to eliminate educator equity gaps.

We hope that states will carefully review our analyses and consider incorporating our suggestions for improvement.

July 13, 2017

Elizabeth Ross

Data, data everywhere but not a drop to drink.

That’s what many principals have concluded after gaining access to more data about teachers’ past performance without understanding how to make the most of it during hiring. A recently published study by Marisa Cannata (Vanderbilt University) and her colleagues at the University of Michigan and North Carolina State University examines this challenge and identifies big and small steps district central offices can take to remedy the problem. Namely, the study highlights the need for districts to communicate about data availability and help principals use data to complement their professional judgment.

The researchers surveyed nearly 800 principals in multiple districts and followed up with a selection of interviews. Many principals are proactive in their approach to gathering relevant data (for example, they may ask applicants to bring previous teacher evaluations with them) and systematic in their approach to assessing a teacher’s fit within their school. One principal describes a clever way to use his district’s evaluation rubric for demonstration lessons:

Other principals may not be as willing to go the extra mile to collect relevant data. In one district, a principal explained that while she didn’t automatically have access to all the data she would like, reaching out to the district office to get that information was quick and easy. A fellow principal in the same district couldn’t say the same—

Districts still have work to do to get principals on the same page about data quality and limitations, particularly when it comes to value-added data. As one VAM-skeptical principal explains:

If this study makes one thing clear, it’s that the distance between data collection and data use is long; bridging that gap will require comprehensive support and ongoing input from building leaders.

June 8, 2017

Stephen Buckley

Studies have shown teachers who have strong academic backgrounds tend to be more successful in the classroom.

January 24, 2017

Sam Lubell

Do low-income students have the same access to effective teachers as their more affluent peers? A new study from Eric Isenberg and his colleagues at Mathematica Policy Research and the Brookings Institution examines this question and draws a surprising conclusion.

In 26 urban districts, the researchers set out to measure the “effective teaching gap,” that is, the discrepancy in students’ access to effective teachers depending on their socioeconomic status (SES). Teacher effectiveness was determined entirely by value-added scores.

Applying this framework, if all students had equal access to effective teachers, the effective teaching gap would be zero. The reality wasn’t that far off the mark and in contrast with the findings from a fair amount of other research. Many (though not all) of the districts turned out to be providing all students, no matter what their SES, roughly the same access to effective teachers.

To the districts’ credit, these results reflected a good deal of work on their part. On average, districts in the study had implemented around five common strategies aimed at promoting the equitable distribution of teachers across schools. They include comprehensive teacher induction, highly selective alternative routes to teaching, targeted use of bonuses, performance pay, and early hiring timelines in high-need schools.

What makes this study so different from others that have pursued similar questions and gotten different results? For one, there were clear methodological differences, particularly when it comes to calculating a teacher’s value-added score. Isenberg’s study controls for peer effects (a measure of how the characteristics of a class as a whole might affect the performance of any one student); however, many other studies do not incorporate peer effects in value-added measures. In addition, this study focused solely on the distribution of teachers within each district, not between them. It did not attempt to answer the question as to an effective teaching gap between urban districts and the suburban districts that border them.

For a detailed discussion of the conflicting literature related to the effective teaching gap, we recommend this CALDER brief, which describes the debate around peer effects, differences in research conducted across vs. within districts, and other methodological points.

January 12, 2017

Autumn Lewis

Teacher quality researchers made plenty of provocative headlines in 2016. They identified trends to monitor, new tips for the trade, and a few wins worth celebrating. Here are the papers we think are the 2016 standouts.

1. Great teachers beget more great teachers

Papay, J., Taylor, E., Tyler, J., & Laski, M. (2016). Learning job skills from colleagues at work: Evidence from a field experiment using teacher performance data.

In one of our favorite experiments of the year from researchers at Brown University and Harvard Graduate School of Education, researchers helped schools identify a teacher who was struggling in a particular area and matched that teacher with someone who excelled in that particular area. Then, they left them to their own devices. No training. No oversight. The paired teachers found a way to work with one another to address deficiencies and grow professionally. In the end, gains for the low-performing teacher were large and persistent from year to year.

2 and 3. And the theme continues: When it comes to professional development, small may be better

Jackson, K. & Makarin, A. (2016). Simplifying teaching: A field experiment with online “off-the-shelf” lessons.

In a similar vein to the simple paired teaching strategy are two other papers, each helping us to better understand how professional development could be improved. They each involved inexpensive, light touch interventions that led to great gains. In the first, from the prolific Kirabo Jackson with his Northwestern colleague Alexey Makarin, teacher performance dramatically improved after they were given access to a library of high-quality, low-cost lesson plans in mathematics, as well as a few emails to remind them to use them. Teachers who also received access but no reminder emails did not use the plans and their performance did not improve. In the second paper, from Stanford researchers, suspension rates plummeted in classrooms taught by teachers who had participated in only a 45-minute online session, in which teachers were prompted to thinking about how to build more positive student-teacher relationships.

Both studies serve as a reminder that when big change is needed, every small step counts.

4. Districts must find better ways to address teachers’ unintended racial bias

Grisson, J.A., & Redding, C. (2016). Discretion and disproportionality: Explaining the underrepresentation of high-achieving students of color in gifted programs.

2016 began with a sobering finding: even when black students have the same high test scores as white students, they are much less likely to be enrolled in a gifted education program. The main culprit is the identification process, relying heavily on teacher recommendations. As we explore in this paper, jointly authored with Brookings researcher Michael Hansen, districts will not be able to hire their way out of this problem, recruiting more teachers of color. The solutions must also include better training of faculty and safeguards to help teachers recognize and overcome their biases.

5. Groundbreaking policy and smart talent management continue to make the District of Columbia a district to emulate

Adnot, M., Dee, T., Katz, V., & Wyckoff, J. (2016). Teacher turnover, teacher quality, and student achievement in DCPS.

Over the last decade, District of Columbia Public Schools (DCPS) has charted new territory in teacher recruitment, retention, and management–and they have faced plenty of pushback and skepticism along the way. But this year the Academy has weighed in with a paper from University of Virginia researchers, surfacing proof that one of their biggest bets is paying off. By letting low-performers go, doubling down on retention efforts, and getting smart about recruitment, DCPS has increased the quality of their teacher workforce substantially. The result is real growth in student learning, surpassing what’s been measured in any other urban district.

6. On the need to get more intentional about student teaching

Goldhaber, D., Krieg, J.M., & Theobald, R. (2016). Does the match matter? Exploring whether student teaching experiences affect teacher effectiveness and attrition.

Our top list wouldn’t be complete without a paper from Dan Goldhaber and company. This year’s top Goldhaber paper looks at student teaching, a much unstudied topic that the researcher and NCTQ both agree deserves a lot more attention. This Washington state study finds that teachers are more effective if they have completed their student teaching in a school that was demographically similar to the school where they would ultimately work. Not only that, but teachers are also more likely to remain in the profession if they student taught in a school that had low teacher turnover. Two important insights for teacher prep programs to ponder.

December 20, 2016

Every consumer knows how the law of supply and demand affects prices. When demand is higher than supply, the price goes up. As suppliers increase production to match the demand, the price goes down.

I’ve frequently lamented how school districts try to exempt themselves from this law. When districts are reluctant to raise the salary to teachers in fields with more demand than supply, such as ELL, special education, and secondary math and science, it is no surprise when they fail to find qualified candidates with these much-needed skills.

Teacher unions and other opponents of salary differentiation have to exaggerate the breadth of this teacher shortage into claims of a general teacher shortage so they can then justify demanding general policy changes. Of course, raising the salary for all teachers, even those in fields with plenty of applicants, is an expensive way of solving a limited problem.

Still, even when districts ignore supply and demand, others don’t. College students, for example. News about teacher hiring and firing does influence undergraduates when they’re trying to decide on a major. A few years ago, during the Great Recession, schools dismissed 220,000 teachers–most of them relatively new hires. People with jobs held onto them tightly, reducing the replacement rate. It’s no surprise that college students decided against a teaching career, resulting in a drop in enrollment in teacher education of 36 percent between 2009-10 and 2013-14.

Today’s college students are hearing a very different story of teacher shortages and plentiful hiring. There’s now some new evidence that this is affecting their choices exactly the way the law of supply and demand would predict.

For instance, the California Commission on Teacher Credentialing found that state enrollment in teacher education increased nearly 10 percent between 2013-2014 and 2014-2015. In Indiana, the number of newly licensed teachers increased 18 percent between 2014-2015 and 2015-2016. It turns out that publicity around teacher shortages actually makes them less likely to occur.

The bad news is that we still won’t do what it takes to address those persistent shortages of teachers who can fill certain subject areas or work in a rural or high urban school. That’s because both higher ed institutions and school districts continue to break the law of supply and demand and should be cause for targeted recruitment strategies, not general alarm.

For instance, higher education programs continue to prepare about twice as many new elementary teachers as are needed to fill openings. They should steer some of these candidates to fields like special education where supply is lower than demand.

There’s no need to lower standards at teacher preparation programs to bring in more teachers. Leave it up to the law of supply and demand to rectify that problem. Instead, states, higher education, and districts should solve the actual, more limited problem of shortages in specific fields by directing candidates away from over-enrolled elementary programs and increasing compensation in specialized areas.

As civics teachers tell their students, everyone is supposed to follow the law.

November 14, 2016

Kate Walsh

If there’s one thing that research has shown us time and again, it’s that being a brand new teacher is hard—and being one of their first students is not all that ideal either. But what happens when an experienced teacher switches to a new grade level or subject? Does she start all over again? This shift, called “churn,” might not sound like a big deal, but as with any change in professional responsibilities, it does come with a learning curve and some predictable consequences.

In a new study looking at data from New York City over a 35-year period, Allison Attebury (UC Boulder), Susanna Loeb (Stanford), and Jim Wyckoff (UVA) find that a student taught by a churned teacher faces a moderate disadvantage. But because 25 percent of the city’s teachers churn to a new grade, subject, or both within their school every year, that moderate difference can really add up to a significant learning loss over several years.

Little Johnny encounters 4-5 churned teachers in grades 3-8, but just one brand new teacher.

As we explored in last month’s TQB, it seems plausible that there could be an upside to shifting teachers to new grades within a school. Maybe Mrs. Jones does better with older students than younger, and so a switch in this instance could help her find a better teaching fit. But unfortunately, this study did not support that hypothesis as a guiding principle. Instead there’s no clear evidence that churned teachers end up performing much better in new positions.

Nevertheless, if we’re not speaking about within-school churn but transferring schools, it may be another story. Susanna Loeb, one of the study’s co-authors, recently published another study with Min Sun (University of Washington) and Jason Grissom (Vanderbilt) that does identify some benefit to moving teachers around. Experienced and relatively effective math teachers who transfer from one school to another create a “spillover” effect—meaning math scores go up for the students taught by the other teachers in that grade level. This finding suggests that there are some ways in which administrators can rethink teaching assignments to improve student outcomes—as long as these shifts are made sparingly and strategically.

November 14, 2016

Kency Nittler, Sarah Brody

One feature of an ideal school environment, we

believe, is that both students and their teachers reflect America in all of its

diversity. Everyone, including children coming from privilege, benefits from a

diverse school experience.

It’s no wonder that as the minority student

population has grown in numbers in the past few decades, surpassing 50 percent,

so many of us are troubled that the minority teacher population has failed to

keep pace, standing now at only 18 percent minority. The push to achieve racial

parity between teachers and students has never been stronger, with urgent calls

from school boards, states, and even the U.S. Department of Education for the

nation to make teacher diversity a top goal for school districts.

This sentiment is understandable, commendable, but

— at the risk of being a wet blanket — not even remotely achievable within the

foreseeable future.

No matter how you run the numbers, school districts

simply cannot recruit and retain enough black and Hispanic teachers to achieve

racial parity between the teacher workforce and the U.S. student body – no

matter how many reprimands HR officials have to face from the their school

boards for the paltry results.

Researchers from NCTQ and The Brookings Institution

recently analyzed what it would take to create a teaching workforce as diverse

as the students it serves. You can find a full report of our analysis and

findings here.

We estimate the effects of different interventions

that might increase the number of minority teachers, extrapolating population

projections for the next four decades to see how close they can come to

creating a racially representative teacher workforce.

The findings are startling: parity or even

significant inroads to parity will remain completely elusive unless we fire on

all cylinders. If we can somehow boost the rates of college completion,

interest in teaching, hiring, and retention so that these rates for black and

Hispanic college students and adults mirror the rates of their white

counterparts, then parity becomes an achievable goal – but is still several

decades away.

How can this be?

Let’s walk through what we found, drawing on a

model we built using U.S. Census projections and data about the current teacher

and student populations to estimate the impact of various interventions.

For example, let’s see where a big push on

retention of black teachers gets us. Currently, 16 percent of America’s public school

students are black, compared to 7 percent of teachers, creating a nine

percentage point gap in the diversity of students and teachers.

What could happen if schools took real and

substantive steps to retain their black teachers so that year in and year out

black teachers stay in the classroom at the same rate as white teachers

(improving their current attrition rate from 10 percent to mirror white

teachers’ 7 percent)? We still wouldn’t close the diversity gap even projecting

out to 2060 (the furthest year of Census projections available).

Next, imagine we committed ourselves heart, body,

and soul (as many districts are, in fact, trying to do) to hire more black

teachers. The rewards would be tiny even projecting all the way out to 2060.

Okay, so what about persuading more black college

students to consider teaching? Higher education could heavily promote teaching

with undergraduates, or graduate programs and alternative providers could

recruit more black candidates—something that many claim to be doing already.

But let’s imagine pouring some real resources into these strategies, such as increased

salaries, loan forgiveness, or more leadership opportunities to succeed in

persuading black adults to consider teaching at the same rate as white adults (currently

4.3 percent of black undergraduate students major in education compared with

6.9 percent of white undergraduates; we see similar disparities for graduate

college education degrees and alternative certification enrollment).

Again, the results would be fairly paltry – closing

the diversity gap by about two and a half percentage points by 2060.

I’m guessing that a lot of people reading this are

thinking “but look at the success of Teach For America, now recruiting new

cohorts which are about 50 percent teachers of color?” TFA was able to achieve

these huge gains in part because it developed unprecedented recruitment efforts

of minority students beginning in their freshmen year—a great strategy to

emulate. But keep in mind that the corps is tiny compared to America’s needs.

Teach For America supplies less than 3 percent of the nation’s teachers. Its

hard push on this problem still only produced about 800 new black corps members

in a year. That’s enough to translate into significant gains for TFA, which is

only recruiting some 4,100 teachers in a year, but remains a far cry from the

300,000 more black teachers needed to achieve parity across all American

schools.

Let’s go back to the point of greatest disparity

between black and white students: the college completion rate. If we invest

heavily to support black students and ameliorate their low college completion

rate so that they graduate college at the same rate as white students

(currently 28 percent of black 22-year olds have earned a bachelor’s degree,

compared with 47 percent of white 22-year olds), we still will not come close

to closing the gap by 2060.

Disheartening, no?

For Hispanic teachers, the dismal scenario is much

the same. In fact because the Hispanic population in the US is growing at such

a fast rate, much faster than the black population, the diversity gap is

expected to widen if we do not take action.

Only if we are able to graduate more Hispanic

teachers from college or draw more Hispanic adults into careers in teaching can

we reduce the growing diversity gap significantly, otherwise expected to be 22 percentage

points by 2060.

Clearly, the answer is to combine all these

interventions and be successful at

all of them (success defined here as achieving the same rates as their white

counterparts) to make any real dent. If over the next decade we were to improve

college completion rates, interest in teaching, hiring, and retention to mirror

that of white teachers at every point, we would actually achieve parity by the

year 2044 for black teachers and students. The picture is less cheery for

Hispanic teachers, only coming within the ballpark (three percentage points

away from racial parity) by consistent pushes through 2060.

So are we

suggesting we all throw up our hands and give up on achieving greater parity?

Absolutely not. But let’s not underestimate the ambition, commitment, and

persistence needed, or browbeat school superintendents or human resources

officials when they are only able to make incremental progress. Let’s also not

advocate for racial parity at the expense of quality. The research is clear

that students’ success still depends most on the quality of their teachers

In the meantime, other important solutions can

achieve greater equity in our schools. Let’s look for meaningful ways to ensure

that teachers – who want to do right by their students – don’t unintentionally

do harm to the kids who don’t look like them. Let’s go beyond the stuff of

current trainings in which teachers and teacher candidates engage in a lot of

reflecting on their implicit biases, analyzing their white privilege, or

developing cultural sensitivity, much of which hasn’t had much impact –

although these do play an important role. Let’s do more to have teachers

examine their daily interactions with students by asking themselves: which

students do they call on to answer questions? Are some students more likely to receive

harsher disciplinary actions than others? Do they select some groups of students

for more challenging work over others? Give teachers the training and tools to

make sure that they do not allow their biases along race, gender, class, or any

other lines to get in the way of helping every child thrive.

August 18, 2016

Hannah Putman, Kate Walsh

For most students, the start of middle school represents

some newfound independence. For the first time, they get to travel the halls

from class to class without being led by an adult.

Of course, this new freedom stems from how middle

schools are set up. Few teachers have the training to teach every subject in

the middle school curriculum so instead of having one primary teacher, there

are at least four. Students find themselves traveling to the teachers, each a

specialist in their subject area.

There’s been a lot of debate over the years about when

to introduce subject specialization. In fact many elementary schools introduce

the model at 4th grade.

But a strong new study from Harvard economist

Roland Fryer calls into question that practice.

Fryer conducted a two-year experiment in 50 public

elementary schools in Houston, Texas. Half of the schools remained on a

traditional elementary school schedule; in the other half, principals assigned

teachers to teach specific subjects based on their observed strengths and

previous value-added scores.

For the most part, assigning teachers to specific

subjects didn’t make much of a difference—and when it did, that difference was

generally negative. Reading and math scores declined, while problem behaviors

and absences actually increased—albeit to a small degree. Basic economic theory

predicted an efficient assembly line in which every teacher installed her

piece; reality told another story.

It’s hard to know exactly why the experiment didn’t

have better results. Perhaps teacher specialization would have a positive

impact if teachers received extra training in their assigned subjects. Perhaps

lost time getting to know each individual student eliminates any benefits that

could come from specialization.

Regardless of the cause, the results serve as a

helpful reminder that elementary

teachers need a strong grounding in all four traditional content areas, not

just the ones they’re more drawn to, as principals can’t simply

rearrange staff based on interest or inclination and expect better student outcomes.

Further, Fryer’s study is robust, using a large sample size, multi-year

implementation, sound experimental design, and realistic policy implementation.

As this study failed to find a benefit to teacher specialization in Houston’s elementary

schools, it’s unlikely that other districts would fare better.

August 18, 2016

Jack Powers

August 1, 2016

Hannah Putman, Kate Walsh

What happens in DC has the potential to

impact districts across the entire nation.

February 16, 2016

Kate Walsh, Laura Pomerance