Imagine you and I are suddenly transported back to first grade. Our teacher hands us a large book with colorful pictures and words across the bottom of each page. We open the book and see a long, squatty creature with dark green scales, a long nose with eyes bulging out the top of its head, and sharp teeth lining its mouth. We read the words below the picture, but one of them is completely unfamiliar to us: “The big crocodile sat by the water on a sunny day.”

We eagerly use the strategies our teacher has taught us when we encounter an unfamiliar word. We think about what would make sense. We look at the picture. Suddenly, it becomes obvious: The big alligator sat by the water on a sunny day! We’re so excited! On we go with the story, convinced that the letters c-r-o-c-o-d-i-l-e represent the word alligator. Our mistake goes unchecked because our guess works semantically in the context of the story.

Instead of helping us read, our teacher just helped us guess the word. But it’s hard to blame the teacher. After all, she was probably trained to teach this method (called three-cueing) to help students learn to read. The problem, of course, is that it’s not really reading at all. It’s guessing. Unfortunately, many teacher prep programs across the country still teach this and other discredited approaches to teaching reading.

After more than five decades of scientific research, we know what works and what doesn’t when it comes to how to teach kids to read. Teachers will be more successful if their reading instruction is grounded in five key components:

- Phonemic awareness: The ability to hear and manipulate individual sounds in spoken words.

- Phonics: Connecting sounds to written letters or groups of letters.

- Fluency: Reading with speed, accuracy, and proper expression.

- Vocabulary: Knowing the meaning of words and how to use them.

- Comprehension: Understanding and interpreting what is read.

Yet in our 2023 Teacher Prep Review: Reading Foundations report, the National Council on Teacher Quality (NCTQ) found that only about a quarter of the more than 700 teacher prep programs we reviewed teach all five components.

Naturally, this has raised questions for some: If they’re not preparing teachers in these five scientifically backed areas, what are programs teaching?

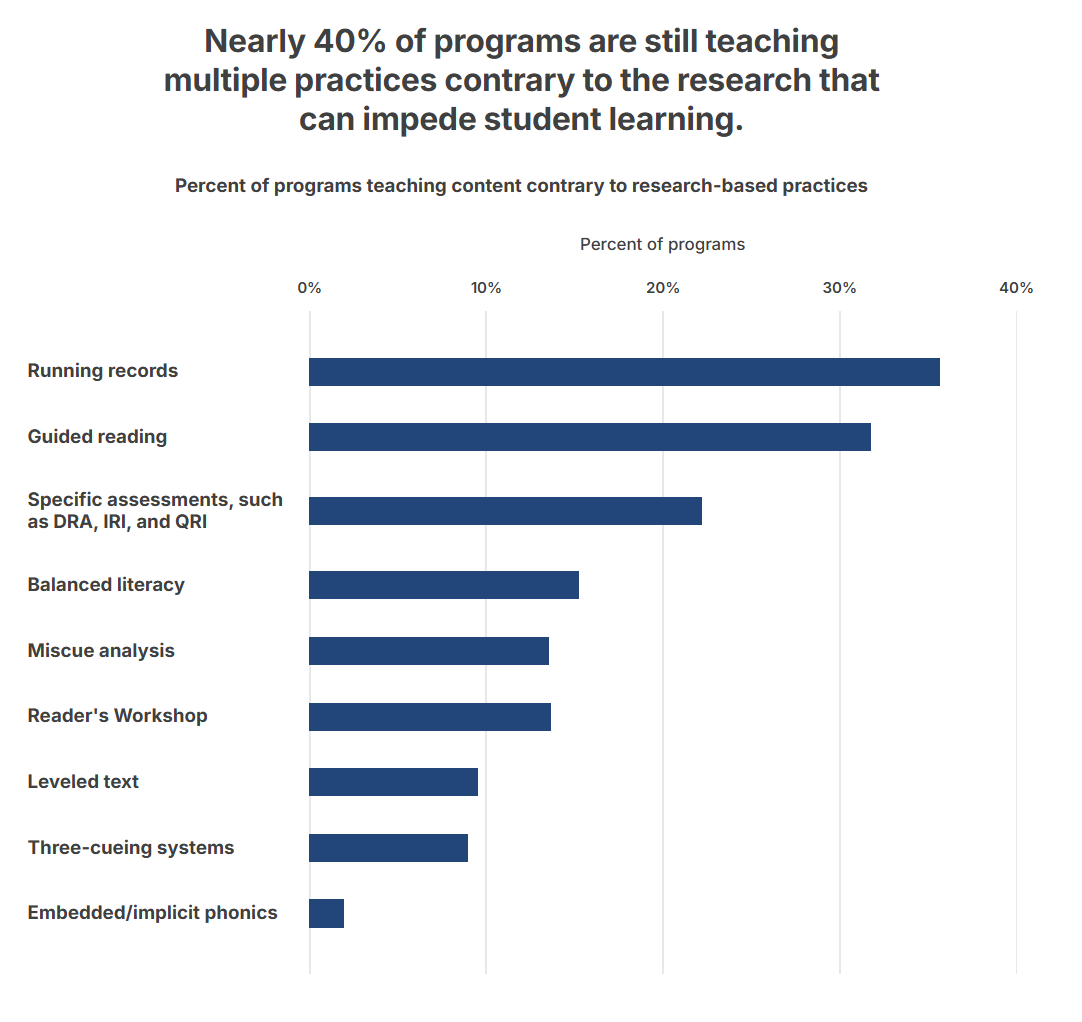

That’s a complicated question, one for which we don’t have a complete answer. However, a portion of our 2023 analysis does shed some light. Working alongside reading experts, NCTQ identified nine instructional practices that run counter to reading research.1 These practices include three-cueing models like the one described above, which encourage students to use pictures and context to guess when confronted with a word they don’t know.2

They also include classroom strategies such as the use of leveled texts, where the teacher assesses students individually to determine their reading level, then assigns them books to read independently or in small groups by level.3 Unfortunately, leveled texts do not help students improve their ability to use phonics skills to sound out and learn new words because they don’t provide multiple opportunities to practice the same letter patterns.4 They encourage new readers to guess or memorize words instead of learning to read them. The use of leveled texts can also deny students access to grade-level content and vocabulary if their reading level lags. This is particularly problematic because the assessments used to gauge students’ reading levels and the tools used to determine the reading level of books are varied and imprecise.5 Leveled texts also fail to address that a student’s interest in a topic can motivate them to read a more difficult text than their reading level may suggest.6

NCTQ’s analysis revealed that 40% of teacher prep programs are still teaching two or more practices that are incompatible with scientifically based reading instruction. Time in a teacher preparation program is precious. In that environment, teacher candidates are sheltered from the high-stakes reality of classroom teaching while they develop their knowledge and skills with support from professors and mentors. It is a tragedy when any of this time is wasted; worse yet, when it is spent teaching aspiring teachers practices that will not help, and may even harm, their future students.

There is a spectrum of programs, from those that are fully aligned to scientifically based reading to those that are fully wedded to debunked reading methods. And there is variation—and confusion—in between. For example, we identified over 200 programs that teach at least three of the five core components of scientifically based reading instruction right alongside at least one contrary practice. Doing so legitimizes ineffective methods and risks confusing aspiring teachers and, more regrettably, their students.

For example, if a student is taught both how to decode words and told to use three-cueing, which strategy are they going to pull out when they come across an unfamiliar word? Will they spend time looking at the picture or considering the context at the expense of practicing decoding? As recently as 2019, an Education Week survey found that most elementary special education and K–2 teachers (72%) incorporate debunked practices into their reading instruction.7 Of course they do! They are taught to do exactly that with hodgepodge teacher prep content.

Then there is the curious case of the more than 100 prep programs NCTQ identified that fail to provide adequate coverage of more than two of the five core components of scientifically based reading instruction, yet also show no evidence of teaching any of the nine contrary practices. A deeper exploration of these programs is necessary to fully understand how they are falling short when it comes to providing teacher candidates with an adequate foundation in scientifically based reading instruction. These programs may provide woefully little course time or experience on reading instruction—or they may be teaching reading instruction strategies that fall outside the strong or contrary practices we look for in our analysis.

Researchers from RAND recently asked K–2 teachers whether their teacher prep programs emphasized teaching reading using phonics and word patterns (strategies associated with scientifically based reading instruction) or using the meaning and context of words (strategies associated with the contrary practices).8 The results were split, with roughly 20% of respondents falling into each camp.9 Just over 30% of teachers felt their programs equally emphasized both sets of strategies, and the rest either couldn’t remember or were not provided any instruction in reading foundations at all.10 Teachers in the same survey also offered a warning for teacher preparation programs: Just 4% of K–2 teachers reported that their knowledge of how to teach reading was most informed by their teacher preparation experience.11

Programs vary a great deal across the country. Take California, for example, a state in which advocates are fighting to safeguard students from discredited reading instruction practices. Across the 41 elementary teacher prep programs NCTQ reviewed in the Golden State, just two programs adequately cover the five core components of scientifically based reading instruction. The average California program covers no more than one of the five core components, while teaching about two contrary practices. It is no wonder reading advocates and experts in California are concerned. Many prep programs are failing to move with urgency, despite the fact that NAEP scores show that less than a third of California’s fourth graders read proficiently.

By contrast, 11 of the 16 programs we reviewed in Colorado adequately cover all five core components of scientifically based reading instruction. The average Colorado program teaches fewer than one contrary practice. It is no surprise that Colorado was one of the 12 states that earned top marks for reading policy in NCTQ’s 2024 state reading policy analysis.

Every child should have a teacher who has been prepared to teach reading with the best methods grounded in science. They shouldn’t be subject to ineffective strategies that will hamper their ability to develop reading skills and perpetuate their struggle into the future. The path to producing effective reading teachers isn’t guesswork—it begins with quality teacher prep.

More like this

The missing link in reading reform: Centering English learners in state literacy policies

The hidden cost of AI-generated lessons: Is AI selling snake oil to teachers?

Black History Month: Learning to read is a civil right

Research that moved minds: Top Teacher Quality Bulletin articles of 2024

Endnotes

- For more information on NCTQ’s Reading Foundations standard methodology, including the nine contrary practices, see Reading Foundations: Technical Report.

- Hempenstall, K. (2006). The three-cueing model: Down for the count? Education News.

- Shanahan, T. (2020). Limiting children to books they can already read: Why it reduces their opportunity to learn. American Educator, 44(2), 13.

- Moats, L. C. (2017). Can prevailing approaches to reading instruction accomplish the goals of RTI. Perspectives on Language and Literacy, 43(3), 15–22.

- Pitcher, B., & Fang, Z. (2007). Can we trust levelled texts? An examination of their reliability and quality from a linguistic perspective. Literacy, 41(1), 43–51.

- D’Souza, K. (2022, November 14). ‘Just-right’ books: Does leveled reading hurt the weakest readers? EdSource. https://edsource.org/2022/just-right-books-does-leveledreading-hurt-the-weakest-readers/680958

- EdWeek Research Center. (2020). Early reading instruction: Results of a national survey of K-2 and elementary special education teachers and postsecondary instructors. Education Week. https://www.edweek.org/research-center/research-center-reports/early-reading-instruction-results-of-a-national-survey

- Shapiro, A & Bellows, L. (2025). Translating reading science into practice—Foundational reading instruction in public elementary schools: Findings from the spring 2024 American Instructional Resources Survey. RAND Corporation. https://www.rand.org/pubs/research_reports/RRA134-28.html

- Shapiro, A & Bellows, L. (2025).

- Shapiro, A & Bellows, L. (2025).

- Shapiro, A & Bellows, L. (2025).