Over and over again, research finds that teachers with master's degrees are rarely more effective than teachers without them. Also true, most teachers (59 percent) accumulate debt in their pursuit of a master's degree. One analysis, that uses data from eight years ago, reports an average debt of nearly $38,000! Quickly escalating tuition costs most likely mean that figure is now higher.

In short, earning a master's degree in education is both ineffective and expensive. Yet, school districts across the country continue to base compensation in part on teachers having a master's degree. This month, the District Trendline looks at the role of advanced degrees in how teachers are paid.

Most districts pay teachers with advanced degrees more

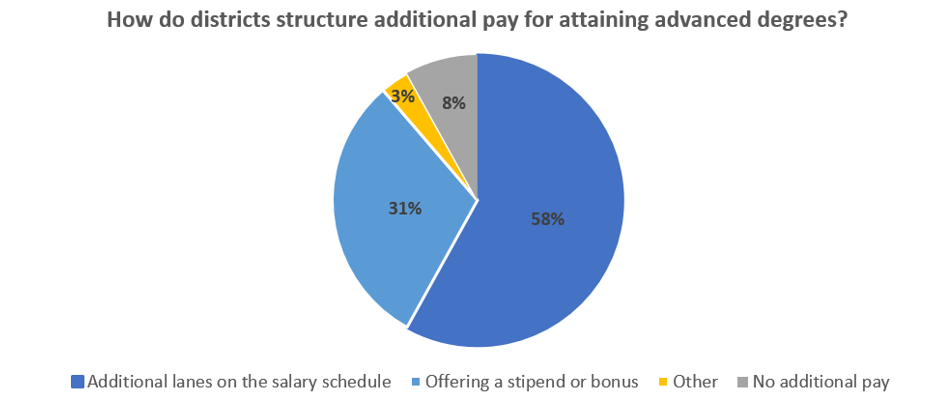

Among our sample of 124 large districts, all but 10 districts (8 percent) compensate their teachers for holding an advanced degree. Most districts (58 percent) structure their salary schedules around them, building "lanes" that teachers can advance through as they earn higher education credits and degrees. In these districts, the additional pay generally fluctuates based on years of experience. In roughly one-third of large districts teachers earn a flat stipend or bonus each year for their advanced degrees.

Of the ten districts that do not offer additional pay, five are in North Carolina (a state that prohibits the practice), with the remainder in several states including districts such as Dallas Independent School District and Hillsborough County Public Schools that have restructured their pay to primarily recognize performance rather than educational credits.

In addition, four districts (3 percent) have non-traditional salary schedules. In these districts, teachers earn credit in a variety of ways to move through the salary schedule, often with advanced degrees or graduate coursework as one of several options teachers can pursue to raise their salaries. Examples include Portland Public Schools (ME) and the Baltimore City Public School System.

The money spent on paying teachers to obtain master's degrees is substantial

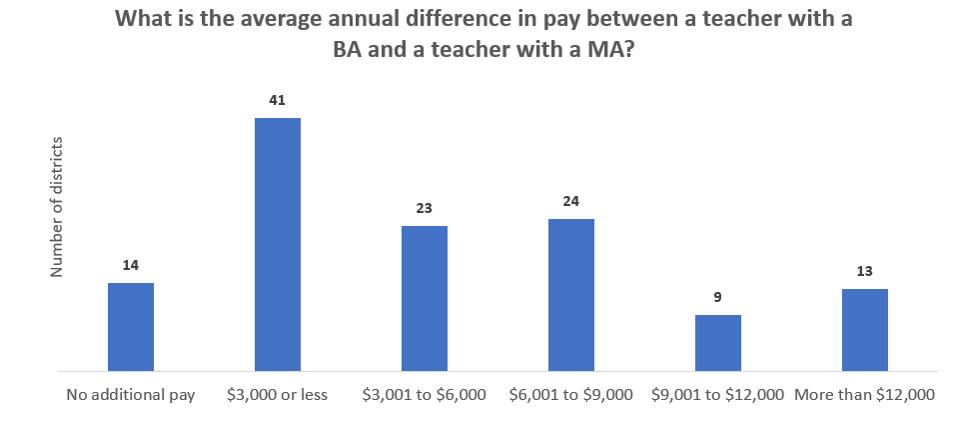

On average, a teacher with a master's degree earns $5,285 more than a teacher with only a bachelor's degree, but that average masks a rather significant range across districts. In Jefferson Parish Public School System (LA), a master's degree only earns a teacher an additional $600 per year, but in Santa Ana Unified School District the annual difference in salary can be over $48,000 towards the end of a teacher's career!

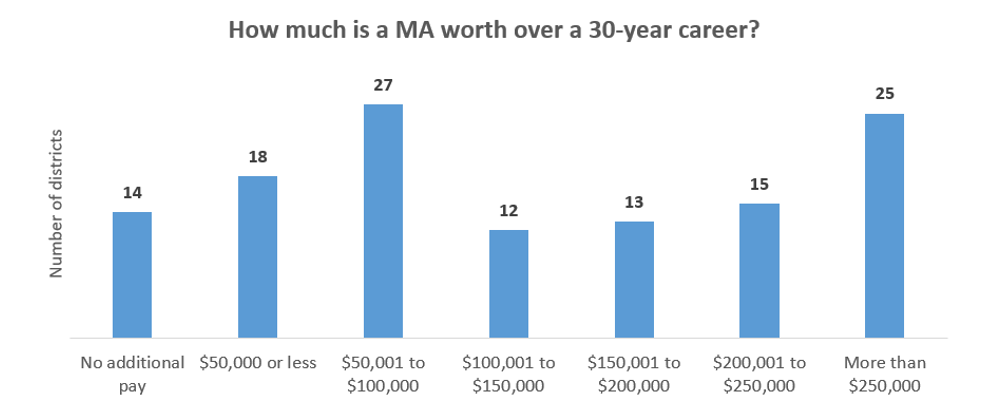

Over the course of a career, these differences add up. Across a 30-year career a teacher with a master's degree will make an average of $158,562 more than a teacher with a bachelor's degree in the largest districts in the country. In fact, there are 25 districts where the master's degree advantage totals more than $250,000, making it entirely understandable why a career teacher would be willing to take on a lot of debt to pursue the degree.

A back-of-the-envelope calculation suggests that school districts across the country are spending over $9.5 billion a year on paying teachers simply for having a master's degree. That's enough money to give every teacher in the country a $2,488 raise each year.[1] That's billions of dollars a year districts are spending that typically do not translate to better student outcomes. As Dr. Marguerite Roza of Georgetown University's Edunomics Lab notes, understanding the tradeoffs in spending is an important and overlooked factor in school finance. Instead of spending that money rewarding teachers for earning ineffective master's degrees, districts could be giving targeted raises to teachers working in hard-to-staff schools and subjects or investing in teacher salaries across the board.

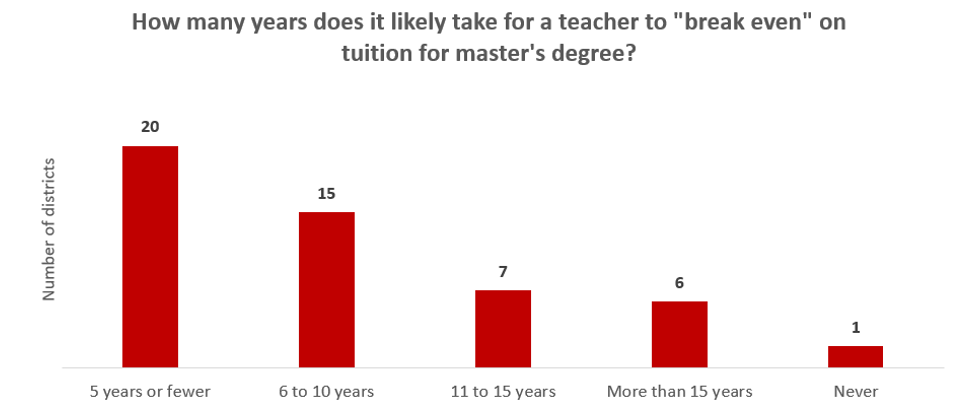

To look at just how quickly a teacher "breaks even" on their investments into obtaining a master's degree, we calculated the average cost of obtaining 36 units of graduate school credit, depending on the location of the district.[2] We were able to get data for 49 of the 110 districts which compensate for degrees.[3]

On average, it takes teachers about eight years to recoup the average cost of tuition for a master's degree, although in about forty percent of the districts with available data teachers offset the cost in five years or fewer.

Districts that allow teachers to recoup the cost of earning higher degrees in short amounts of time are sending a strong signal to their teachers that they should go back to school, regardless of the quality of the classes they will take or their desire to add an additional responsibility to their already busy professional lives.

States are also incentivizing teachers to earn advanced degrees

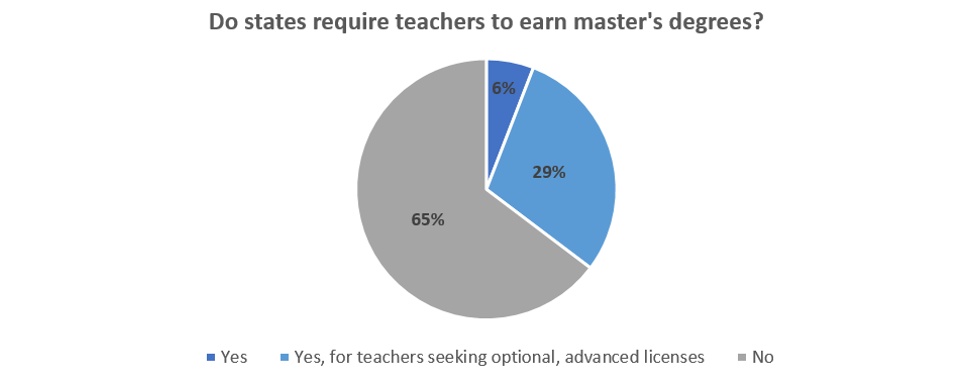

States have a role to play in this story as well. A third of states attach earning a master's degree to their license structures. Only three states (Connecticut, Maryland, and New York) require all teachers to earn a master's degree to keep their license in good standing, down from eight states in 2011. The remaining 15 incentivize such degrees by making them a requisite for obtaining an optional advanced license.

Both districts and states should consider how their policies around teacher compensation and licensure reward, or even require, teachers to earn master's degrees. In light of the consistent evidence that advanced degrees generally have no impact on teacher effectiveness, reconsidering their role in teacher compensation could create a new pool of money that could instead be used strategically to attract and retain a strong teacher workforce.

To see the district-level data included in this piece, click here.

[1] In the 2015-2016 school year there were just over 3.8 million teachers, 47 percent of whom held master's degrees. If the average teacher with a master's degree earns $5,285 per year in compensation for that degree, that results in $9.5 billion being spent on paying teachers more for earning a master's degree.

[2] Using 2017 IPEDS data, we took an average of the cost of tuition of 36 graduate credits for each university with data located in the same city as the district central office.

[3] This is a similar analysis (with similar findings) to one by Matt Chingos in 2014.