About a year ago, I spent the day at an elementary school in Boston to learn from the teachers and administrators about their shift to scientifically-based reading instruction. I was struck by their reflection: “At its core, our shift was one towards a more equitable education for our scholars.”

In the aftermath of the pandemic, this approach of centering equity is paramount. Recent NAEP data shows that only 33% of our 4th graders are reading proficiently, confirming other reports that overall reading proficiency has declined, and that the gap has widened even more for many groups of students already furthest from opportunity. This dismal data has nothing to do with the students and everything to do with inequities in access to effective literacy instruction.

The science is settled on how to effectively teach children to read, and as NCTQ wrote in 2019, this case should be closed. Decades of research and hundreds of studies confirm the way to teach students to read is through scientifically-based reading instruction (SBRI)—explicit, systematic instruction in five core components: phonemic awareness, phonics, fluency, vocabulary, and comprehension. No single component stands alone.

What many still don’t recognize is that teachers’ reading instruction changes the wiring in children’s brains.Teachers have the potential to shape the neural pathways in children’s brains to support skilled readers (or conversely, teachers could reinforce neural pathways and processes that are used by struggling readers).

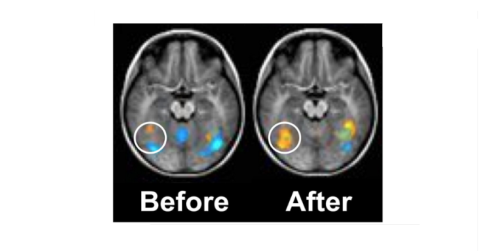

A groundbreaking study by cognitive neuroscientists in 2015 provides evidence that when beginning readers are taught to focus on letter-sound relationships (or phonics), this activates the brain’s circuitry in the left side of the brain, which includes the visual and language regions. These findings show us that providing a phonics foundation stimulates the brain in ways that change the neural pathways to support more efficient and effective readers.*

It is no overstatement to say teachers, like neurosurgeons, have the capacity to change brains. And just as we wouldn’t train neurosurgeons in operating procedures that have much lower success rates, we shouldn’t train teachers in literacy instruction that doesn’t produce the highest number of successful readers.

Unfortunately, numerous surveys of practicing teachers find substantial gaps in their knowledge of SBRI—not for any fault of their own, but because they (like students) were not taught. Worse, many teachers are taught methods that are not aligned with the science and many districts ask teachers to use reading curricula that promote disproven practices (but I will hold that part of the story for another day).

Teachers have been ill-served by a field that has led them away from the reading practices that will best serve their students. A 2019 survey found 68% of teachers and 57% of postsecondary instructors identify “balanced literacy” as their philosophy for teaching early reading, compared to 22% from each group who identify “explicit, systematic phonics.” In the fall of 2021, the American Federation of Teachers conducted a survey of its members that confirmed the need to support teachers to effectively teach reading. Among teacher respondents who provide reading instruction, only 44% of teachers feel “fairly well prepared” or “very well prepared” to teach reading to struggling and below-grade-level readers in their classes.

Teachers care fiercely about creating opportunities for their students, and we must give them the tools to succeed. We must accelerate our efforts to prepare current and aspiring teachers to teach reading using scientifically-based reading instruction and support aspiring principals to provide the conditions in the school for these methods to take hold. And we need to stop funding and using methods and programs that are disproven (I’m looking at you, Massachusetts, with a $600K line item in the state budget for Reading Recovery).

In the upcoming months, NCTQ will release two sets of work focused on strengthening literacy instruction that target one of the most influential institutions in the education field: teacher preparation programs. Specifically, we ask whether preparation programs are giving aspiring elementary teachers 1) the background knowledge they need to support students’ reading comprehension, and 2) the skills and knowledge to teach reading using scientifically-based practices:

- Teacher Prep Review: Building Content Knowledge (Winter 2023): Elementary teachers need content knowledge in science and social studies, both to build their students’ understanding of the world and also to support students in becoming strong readers. With the upcoming Building Content Knowledge Tool, teacher preparation programs can identify actionable solutions for strengthening elementary teacher candidates’ science and social studies content knowledge. The tool will provide programs with a personalized analysis of 1) whether the program’s requirements or institution’s general education requirements cover key content, and 2) guidance on which courses the program could require or recommend to best prepare their teacher candidates to teach the breadth of elementary curricula, and, ultimately, boost students’ reading comprehension.

- Teacher Prep Review: Reading Foundations (Spring 2023): This standard will provide feedback on the degree to which elementary teacher prep programs provide instruction and practice on the five core components of effective reading instruction, as well as whether programs are teaching reading practices that run counter to scientifically-based reading instruction. To update this standard, NCTQ worked with reading experts, including teacher prep faculty, and gathered feedback through an open comment survey with well over 200 respondents across the field. We are particularly interested in finding evidence of exemplary programs to highlight what excellent reading preparation looks like and to identify programs that support a range of learners, such as multilingual students.

Experts estimate if we taught children to read using the scientific practices established over many decades, we could reduce the rates of struggling readers from three in ten children to one in ten. We have the knowledge to do this. Do we have the will? If so, we could upend inequities and change the trajectory of students’ lives. What are we waiting for?

*Hear more on reading instruction in the latest podcast, “Sold a Story: How Teaching Kids to Read Went So Wrong“ by Emily Hanford and Christopher Peak. Their reporting led me to this study.

More like this

Messaging from reading advocates comes off as lopsided. The science isn’t

Getting districts and teacher prep on the same page on reading pays off

Back to the basics to boost reading results: Q&A with TSU’s Dr. Jerri Haynes