From 2009 to 2015, states across the country adopted teacher evaluation reforms for the purpose of making evaluation more meaningful. Historically, teacher evaluation has been a seriously underutilized tool, where virtually all teachers received the same rating and almost no one was provided with actionable feedback. Teacher evaluation reforms—such as increasing the number of ratings teachers could earn, increasing the frequency of evaluations, and incorporating objective measures of student growth—sought to provide more nuanced and comparable data that would both help teachers improve their practice and support efforts to distribute teacher talent more equitably among all students.

In NCTQ’s newly released report, part of our State of the States series, we find that a large number of states have backed away from many of their recent evaluation reforms. The decisions by 30 states to withdraw some of their new evaluation requirements puts the onus squarely on school districts to make teacher evaluation a more meaningful process.

In this month’s District Trendline, we examine some key characteristics of teacher evaluation systems in the nation’s largest school districts, and how those characteristics align with what research indicates makes teacher evaluations most meaningful.

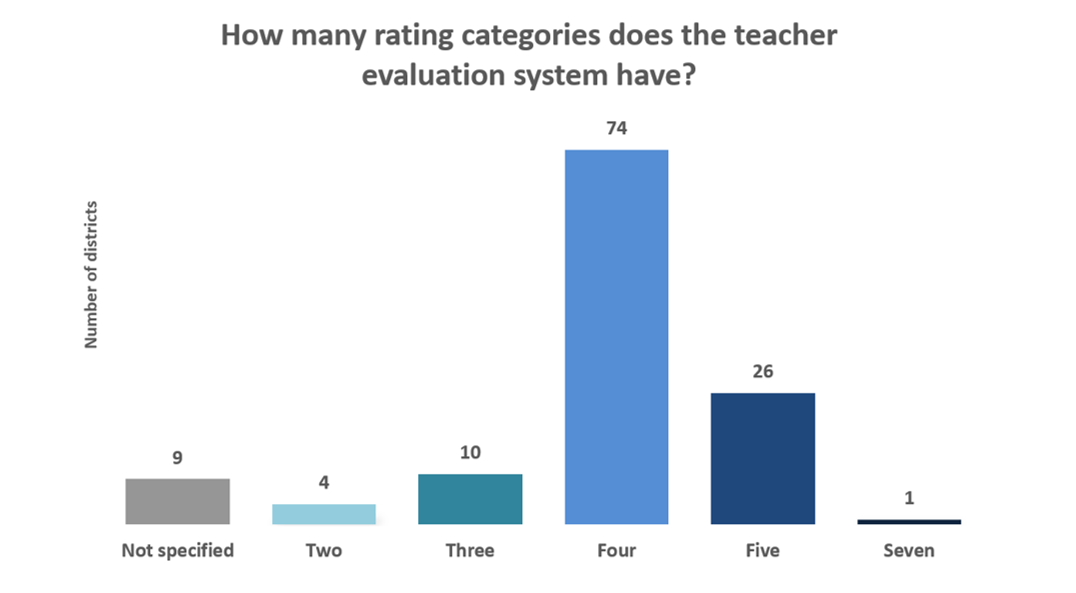

Rating categories

Since 2011, most states have required that teacher evaluation systems have more than two rating categories. School districts have overwhelmingly adopted this policy, with 90 percent of large districts requiring at least three rating categories for teachers and most more. Having more than two rating categories, as compared to binary evaluation systems, increases the useful information available to individual educators and policymakers.

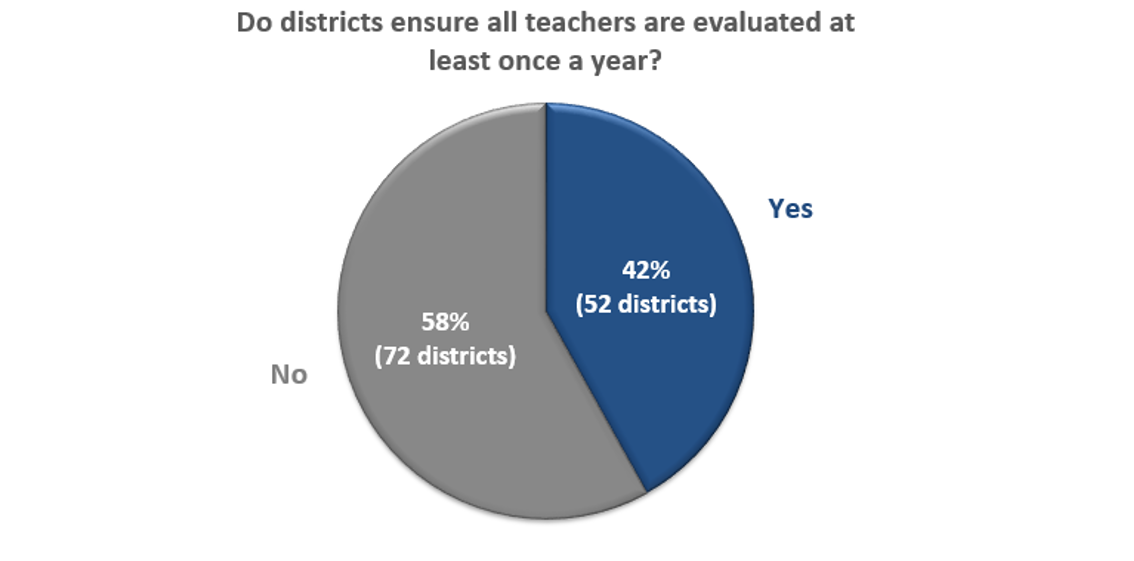

Frequency of evaluations

Annual evaluations benefit all educators, regardless of effectiveness levels. Unfortunately, most states no longer require that all teachers are evaluated each year. Only 42 percent of large districts ensure all teachers get this regular feedback. While these districts almost all require that inexperienced, untenured, or teachers with less-than-effective ratings are evaluated annually, it is more common to exempt experienced teachers with a satisfactory rating on their record. In 21 of the 124 districts we track, teachers can go without a formal evaluation for five years!

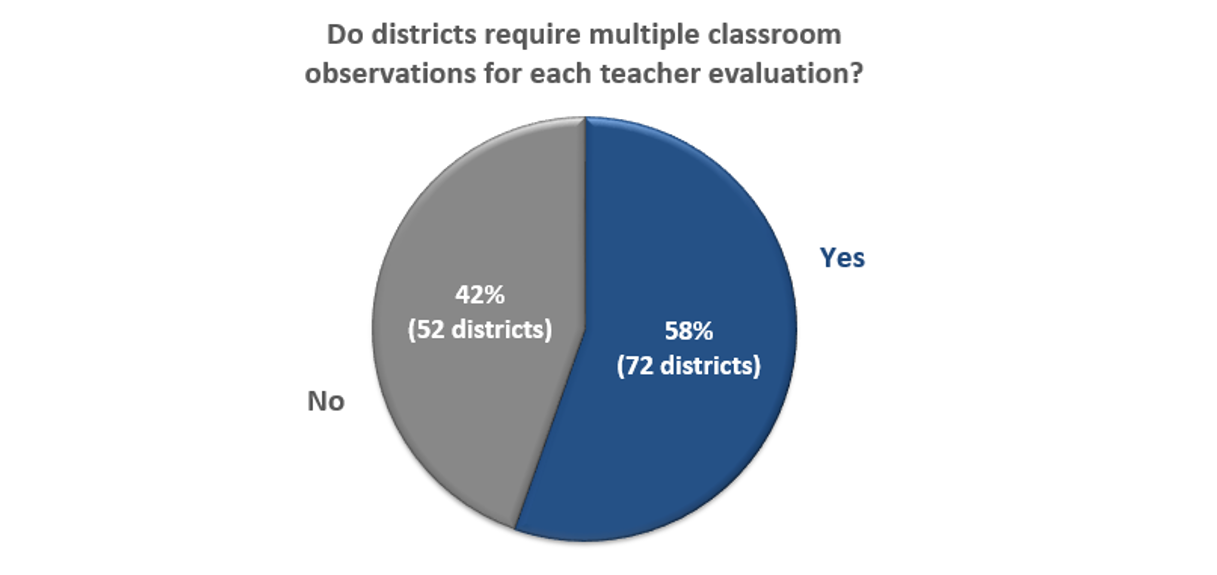

Classroom observations remain a staple of teacher evaluation. The reforms adopted between 2009 and 2015 upped the ante, based on evidence that it takes multiple observations to produce a valid assessment of performance. Most states and, in turn, most large districts (58 percent) still require teachers to be observed multiple times as part of an evaluation. These observations can be formal or informal walk-throughs, and most often include a feedback conference between the teacher and their observer.

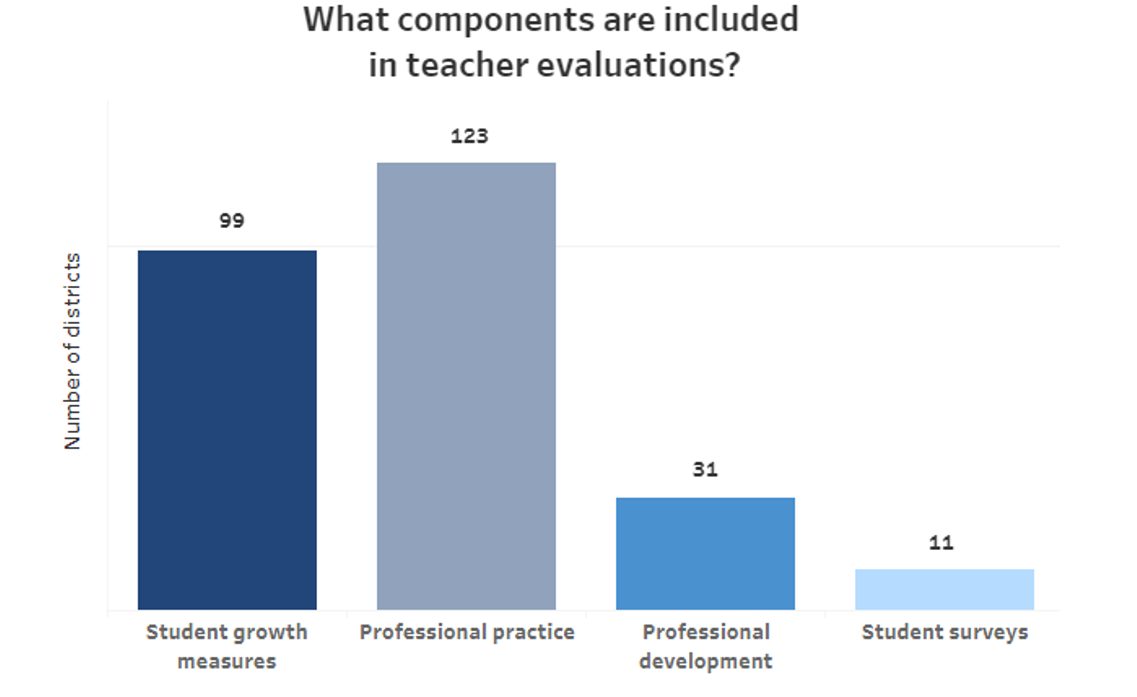

Teacher evaluation components

One of the most controversial topics in teacher evaluation over the past several years has been what components should be factored into a teacher’s rating.

All the large districts in our sample of 124 except one1 require a measure of ‘professional practice’ to be included. Professional practice is typically based on classroom observations and rates teachers in areas such as curriculum, instruction, lesson planning, classroom environment, student and family engagement, and professionalism. It most often makes up 50 percent of a teacher’s evaluation, but counts for 100 percent of the evaluation in 16 large districts.

Student survey data provide important information about a teacher’s performance. Seven states require student surveys be factored into teacher evaluations, and another 24 states explicitly allow student surveys. However, of the 48 districts in our sample located in states that explicitly allow student surveys, only four districts use them in their teacher evaluations: Albuquerque Public Schools (NM), Denver Public Schools (CO), Greenville County Schools (SC), and Shelby County Schools (TN).

Four large districts include all four measures (student growth, professional practice, professional development, and student surveys) in their teacher evaluations: Alpine School District (UT), Granite School District (UT), Mobile County Public Schools (AL), and Shelby County Schools (TN).

Digging in to student growth

Among the major evaluation reforms of the past decade was the inclusion of objective measures of student growth. In 2015, 43 states (including the District of Columbia) required objective measures of student growth in teacher evaluation systems, but that number has since dropped dramatically to 34 states.

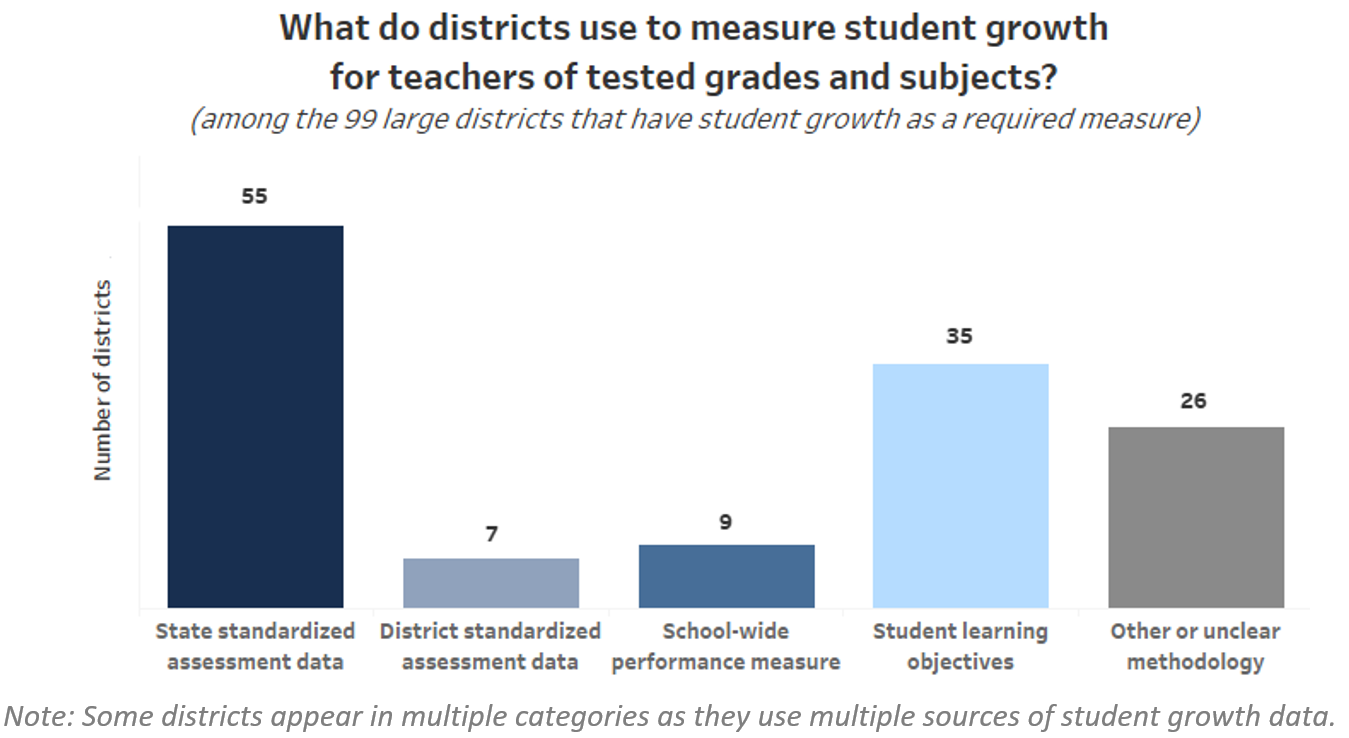

Absent state requirements, it falls to districts to determine how to measure student growth. Student growth measures as required in district teacher evaluation systems (illustrated above) are not necessarily objective, as they often rely on subjective measures such as student learning objectives set at the classroom- or grade-level.

Objective measures of student growth based on state and district-wide standardized assessments (often calculated as value-added measures or student growth percentiles) substantially improve the validity of evaluations and help capture the more genuine range of educator talent within a school, district, or state. Currently, 44 percent of large districts specify that a state standardized assessment is used to measure student growth for teachers in tested grades and subjects, while 28 percent use a measure based on student learning objectives that are established by individual teachers, generally with the approval of their principals.

Neither the optimal ratio of objective to subjective data nor the optimal mix of data sources are firmly established in the research. However, objectivity and comparability of teacher effectiveness data make it easier to determine the targeted support a teacher needs to improve her practice and for education leaders to make the personnel, compensation, and resource allocation decisions that best serve both teachers and students.

Read the new NCTQ State of the States 2019: Teacher and Principal Evaluation Policy for the full set of findings on changes in state educator evaluation policies.

Explore teacher evaluation policies in the nation’s largest districts for yourself with the Custom Report Tool on the Teacher Contract Database.

See examples of best practices in teacher evaluation systems in Making a Difference: Six Places Where Teacher Evaluation Systems are Getting Results.

More like this

Districts are facing hard choices: How can teacher evaluation help?

Rural teacher evaluation system shows promising results for students struggling in math

Put me in, coach! How practice plus coaching helps aspiring teachers win

When it comes to Chicago students, patience may not be a virtue

Endnotes

- In Corona-Norco Unified School District (CA), the teacher and evaluator meet at the beginning of the year “in order to agree mutually upon the elements of the evaluation.”