Not all teacher turnover is created equal. Some turnover is a good thing. Too much of it is a bad thing.

The timing of turnover also matters, meaning a teacher who leaves in June will not hurt learning as much as the teacher who leaves mid-year.

Yet when researchers have studied teacher turnover, these timing issues have been largely neglected. Two new studies by Christopher Redding (University of Florida) and Gary T. Henry (Vanderbilt University) break some new ground, estimating the impact of mid-year turnover on students.

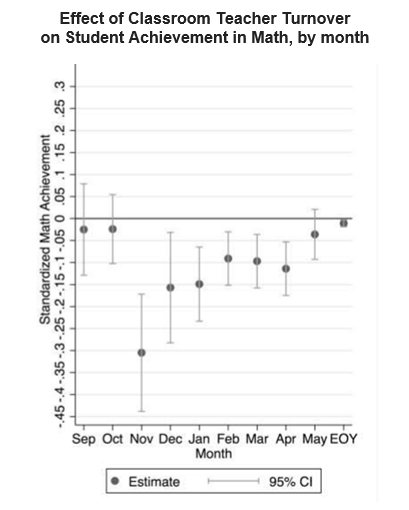

Using data from North Carolina, Redding and Henry’s findings suggest that the roughly 5 percent of teachers who leave mid-year account for the bulk of negative effects of teacher turnover. Students whose classroom teacher left mid-year experienced significantly lower gains than those who had the same teacher for the entire academic year. Teacher turnover at the end of the year, however, had minimal effects on student achievement.

Interestingly, the month of November appears to be a turning point. If a teacher leaves before November, learning doesn’t appear to suffer much. That’s a useful pearl of wisdom for principals who see early on that a teacher clearly isn’t going to make it, but mistakenly put off the decision.

Taken from: Henry, G. T., & Redding, C. (2018). The consequences of leaving school early: The effects of within-year and end-of-year teacher turnover. Education Finance and Policy, 1-52.

A big part of the churn that occurs is among newer teachers assigned to the most challenging schools. When districts insist on placing them in challenging schools, they might as well start a countdown clock, as 4 in 10 are gone by mid-year.

This month we also examined another study on this topic from Lucy Sorenson and Helen Ladd (with CALDER) examining how schools tend to respond to high rates of teacher turnover. They do so not by expanding class size but by hiring yet more novice teachers, which may just expand the likelihood for churn. They also are more apt to hire teachers with provisional or alternative licenses.

All of the studies offer the usual menu of policy responses, including better mentorship programs, providing teachers with consistent feedback, and promoting relationships between teachers and their school communities—to which we would add earlier observations of new teachers and assigning fewer new teachers to the hardest schools.

More like this

Building a school climate that makes teachers want to stay

Does removing tenure lead to a retention problem?