Orange County Public Schools in Florida was already on spring break when the state announced the emergency closure of schools due to the COVID-19 outbreak. Still, within days the school district and the local teachers union signed a memo of understanding, putting in place some initial policies for teachers to work remotely to deliver distance learning to students.

The hastily drafted MOU specified that teachers would continue to be paid, could work from their homes, and would be given access to resources on distance learning. It also set forth a clear expectation that teachers should be available to their students at least three hours a day.

Many issues, few of which a district could have anticipated in the early days of the pandemic, remained. As Orange County began to more clearly articulate expectations for teachers, establishing an Instructional Continuity Plan directing teachers to “make a good faith effort” to both take attendance and grade student work, the teachers union insisted that the district return to the bargaining table. On March 31st, when the district did not respond, the union filed a class-action grievance.

Understandably, the sudden closure of schools has been both immeasurably difficult and confusing for students and adults alike. The first priority for most school districts has been ensuring the safety and nutrition of their students, but now the focus is increasingly on how to keep students learning—and that requires forging teacher policies to address issues about which no one had ever given much thought.

The speed and formality of policy-making during this crisis in Orange County comes in part from a prescient provision in the collective bargaining agreement: “In the case of an infectious disease outbreak that affects the District’s workforce, the procedures in the Emergency Procedures Manual shall be followed. If a school or work location has cause to be shut down because of an outbreak, the CBLT shall meet in an emergency session to bargain the impact.”

Orange County was in a rare if not unique position that required the district to start working with the teachers union immediately to hammer out expectations for teachers. For most school districts, however, the process has been more ad hoc.

Since 2007, the National Council on Teacher Quality (NCTQ) has been collecting, analyzing, and comparing teacher collective bargaining agreements and board policies in large school districts. When this crisis hit, we asked what, if anything, districts had spelled out in their existing policies relevant to teacher work, pay, and leave in situations of emergency school closures. Then we started collecting the new policies districts are adopting for teachers.

Here we present the first round of analysis, focusing on 41 districts to start. We’ll add more in coming weeks, as well as provide updates on the districts in this analysis as they become available.

What existing policies did districts have in place to deal with emergency closures?

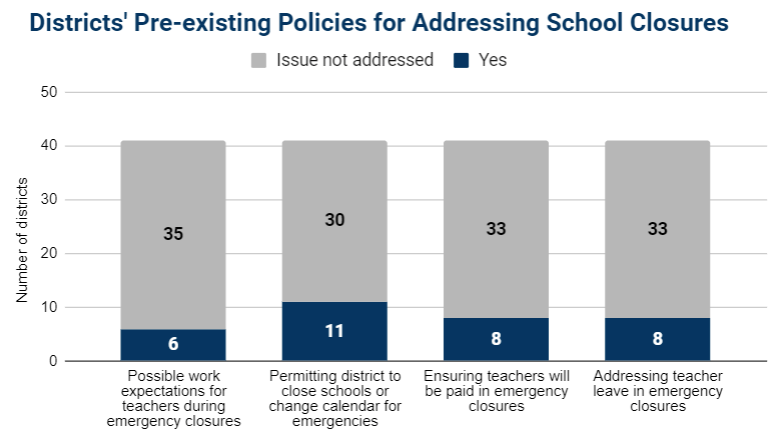

Our initial analysis of 41 large districts across the country finds that most districts did not have pre-existing policies in place to deal with this crisis. Fewer than half had any policies that addressed teacher work expectations, pay, or leave in the case of a non-weather-related emergency school closure.

Among the districts in the sample that made any references to the rules that apply to teachers during an emergency closure:

- Six had possible work expectations for teachers (Anchorage, Atlanta, Kansas City (MO), Minneapolis, Orange County (FL), and Toledo), such as noting that teachers are not expected to report in emergencies, that some district employees may be expected to work in an emergency, and requesting that teachers volunteer for extra duties and assignments. The only district that had a policy permitting teachers to work remotely was Anchorage.

- Eight specified that teachers would continue to be paid: Anchorage, Cincinnati, Indianapolis, Miami-Dade, Montgomery County (MD), Oakland, Shelby County (TN), and Toledo.89

- Only eight90 districts mention teacher leave policies during emergency school closures, but most of these are clearly not applicable for this long-term situation of remote work. Broward County (FL) and Wichita (KS) stand out for having special policies for granting additional leave to impacted teachers in declared local, state, or national emergencies.

Of the 33 districts in the sample that collectively bargain (the remaining eight are in states which do not permit collective bargaining, instead leaving the decisions up to state legislators and school boards), Orange County was the only one where the collective bargaining agreement required the district and union to bargain new policies for teachers for the emergency closure. Another four districts (Albuquerque, Long Beach, Minneapolis, and Shelby County (TN)91) have collective bargaining agreements that require consultation or negotiation with their teachers union for any changes to the school calendar due to emergency situations.

Are districts working with their unions on new policies?

As of writing, seven of the 33 districts in the sample that collectively bargain have entered into formal agreements with their teachers unions: Hawaii (which is organized as only one school district), Los Angeles, Miami-Dade, Orange County (FL), Saint Louis, San Diego, and Seattle.

At least two additional districts are in the process of bargaining: Boston and Long Beach. Another five districts (Albuquerque, Minneapolis, New York City, Newark, and San Francisco) appear to be informally cooperating with their teachers unions to issue joint statements, FAQs, and guidance to teachers.

No doubt, these numbers will change in the next few weeks. Districts are in the process of clarifying what teacher work and remote learning looks like and the space is changing rapidly. On April 1st, California Governor Gavin Newsom and state teachers unions issued guidance for districts and their unions in negotiating new policies for these new and difficult circumstances.

Even without formal negotiations with unions, however, almost all the 41 districts in the sample are working to clarify teacher expectations. Many states are providing guidance, such as California, Illinois, Massachusetts, and New Mexico, but as in many areas of teacher policy, it is up to districts to establish the specifics as it applies to their schools and teachers.

How are districts adapting various teacher policies to the new reality?

We reviewed available MOUs, online communications to teachers, and plans for transitioning to distance learning that districts have posted online to ascertain what policies districts are now adopting for teachers during the closures—with or without a formal agreement with the union.

Nearly all (36 of 41) have officially communicated that teachers will continue to be paid throughout the closure period, and nearly all are communicating clear work expectations for teachers,92 such as working from home requires teachers to plan lessons, prepare instructional materials, and communicate regularly with students. The definition of “regularly” is not currently clear. Minneapolis, for example, has specified that teachers will reach out to students daily, but most districts do not define “regularly.”

Delivery of online lessons. Much has been written about districts struggling to implement distance learning in such a short time, lacking much-needed infrastructure. The Center on Reinventing Public Education (CRPE) has put together and is regularly updating a database of districts’ distance learning plans, and those data, as well as teacher surveys and news reporting, indicate that the start of these plans has been rather chaotic.

Based on the online evidence available, it appears the average time between school closure and distance learning resources starting to become available to students was eight school days. Three districts in our sample appeared to have no downtime, immediately starting distance learning plans they had earlier organized: Atlanta, Gwinnett County (GA), and Miami-Dade, (though Miami-Dade has been criticized for leaving some students behind).

There is significant variation, however, in the types of resources districts are providing to students. Data from CRPE show that nearly all districts are providing academic materials for students and an increasing number of districts are now offering formal curricula, but still very few have already transitioned to teacher-led instruction.

Grading student work. The issue of whether or not teachers should be grading student work during distance learning is a difficult one due to issues of equity and access. As of this writing, 16 districts from the sample have specified that teachers of at least some grades and subjects will grade student work, while six have specified that student work will not be graded (Fairfax County (VA)93, Guilford County (NC), Long Beach, Oakland, Washoe County (NV), and Wichita).

As more states extend the emergency school closures through the end of the school year, decisions to not require teachers to do any grading may have to be reversed, at least for high school classes and high school seniors in particular.

Among the 16 districts that have communicated that teachers of some grades and subjects are expected to grade student work, Aurora Public Schools is one example of clarifying that only high school courses will be graded. Others, such as Seattle Public Schools, specify that teachers should make use of portfolio or other project-based assessments. The District of Columbia, Los Angeles, and San Diego are implementing “no penalty” grading, where completed work can only increase a student’s grade. A few districts, such as Minneapolis and Newark, have communicated that teachers should maintain regular assignment and grading expectations.

Leave Policies. Federal action to expand the Family and Medical Leave Act (FMLA) has provided additional security for teachers, but with teachers now working remotely and on varying schedules, districts are faced with needing to clarify regular leave policies.

Ten of the districts in our sample have communicated that expectations are that teachers will schedule and take personal, sick, or other leaves as usual during the closure period and distance learning. In other words, it appears these districts expect their teachers to work the hours dictated in their contract regardless of any home constraints.

Five districts—Los Angeles, Miami-Dade, New York City, Orange County (FL), and San Diego—have articulated more flexible leave policies, such as not requiring teachers to take half-day leaves, not requiring doctor’s notes, or appreciating that teacher work hours need to be flexible around the needs of caring for their own children or family.

Looking ahead. As more districts initiate distance learning plans and additional policy needs arise, there will no doubt be more to clarify for teachers. After the initial shock of transitioning to working from home and teaching students remotely begins to wear off, there will be new challenges, among them hiring, professional development, and teacher evaluations.1 Florida and Louisiana are two states that have already waived teacher evaluations for the school year, and they likely won’t be the only ones.

In the coming weeks, NCTQ will continue to monitor districts’ policy responses for their teachers, with the hope that we can learn lessons and communicate useful examples to others working to respond to these unprecedented challenges.

Footnotes:

Endnotes

- Late on Wednesday, April 8th, Los Angeles Unified School District and their teachers union (UTLA) reached an agreement that addresses both professional development and teacher evaluation during the closure. Required professional development “shall be limited to Distance Learning strategies and use of technology during the month of April. Any required professional development shall be no longer than one hour and will take the place of any faculty/department/grade level meeting scheduled for the same week.” Teachers in Los Angeles who had completed the evaluation requirements “up to and including the Formal Observation” before the closure will receive their ratings, but those who had not will have the opportunity to push their evaluation to next year.