Working conditions play a crucial role in teachers’ wellbeing, especially after 18 taxing months of reinventing education. In a recent EdWeek article, teachers cited two factors as important for their wellbeing on the job: more time to plan or catch up and smaller class sizes.

Although system-wide class size reductions are not cost effective, targeted class size policies might make a difference to the kids most impacted by COVID and provide some relief to weary teachers. In this District Trendline we look at the contractual obligations of 148 school districts for class sizes. Our sample includes the nation’s largest 100 districts, the largest district in those states not otherwise represented, as well as the districts that are members of the Council of Great City Schools.

The progression of class size limits

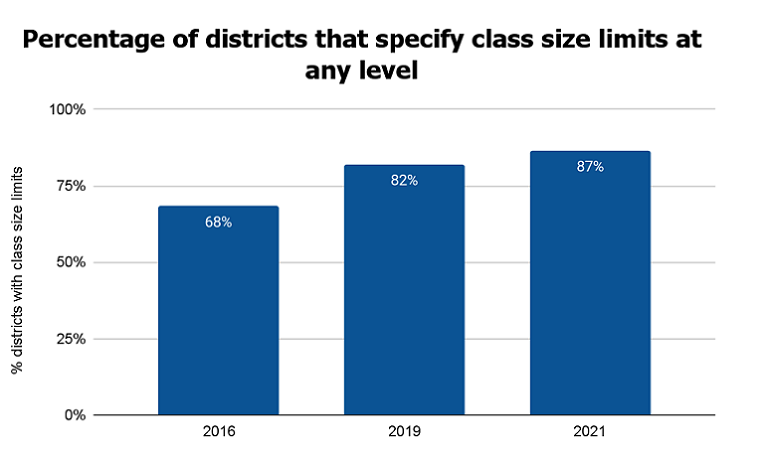

Over the last five years, more districts have chosen to establish limits on class size. In our sample, the percentage of districts that have defined a class size limit for any grade or subject has increased from 68% in 2016 to 87% in 2021—a sizeable jump.

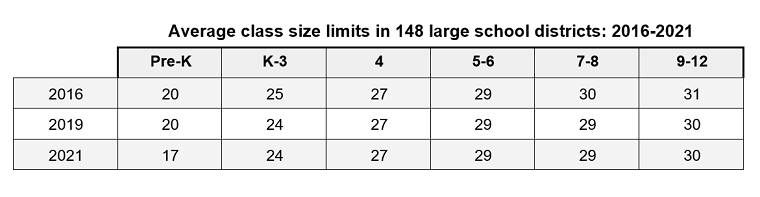

Although according to the National Center for Education Statistics actual average class sizes and pupil/teacher ratios have decreased over the last 10 years, the maximum number of students permitted by class size limit policies—generally found in teacher contracts and school board policies—has not changed much, and even those districts that have recently added limits are not pushing to set lower maximum class sizes.

The following table shows how the average class size limits have remained relatively constant since 2016. Only at the Pre-K level has there been a trend to decrease class sizes: In 2016 Pre-K average class-size limits stood at 20 students, and today that average stands at 17.

The likely source of this decrease is not necessarily the pandemic, but the state of Texas’ recent reduction of class-size limits—plus its districts’ significant role in our sample. In 2019 the state approved an investment of close to a billion dollars to overhaul early childhood education, which included an expansion of their Pre-K programs, with class sizes now capped at 11 students.

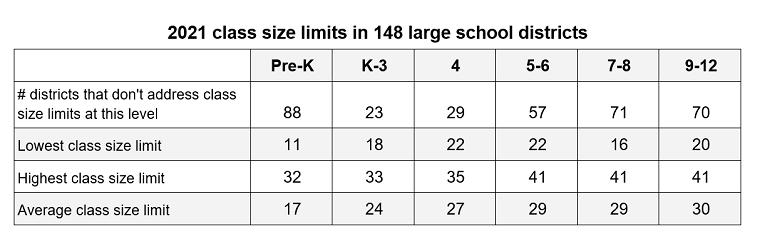

At the other end of the spectrum would appear to be Capistrano Unified School District in California, whose teacher contract spells out a maximum class size of 32 students in a Pre-K class. Presumably the district provides those teachers with at least an aide or two (though we could find no contractual obligation to do so).

The smallest class size limits in grades K-3 are found in Florida school districts, as well as Cincinnati and Minneapolis Public Schools, where there is a limit of 18 students. Contrast those districts with Capistrano again, San Bernardino, and Stockton Unified (all in California); Buffalo, New York City, and Wichita Public Schools in Kansas—all districts that allow up to 30 students in K-3.

Most districts have set policies that align with the research demonstrating the greatest academic benefits can be found by setting lower class size limits for younger grades. Typically, districts will establish clear limits in K-3 and begin to set higher limits starting in 4, 5, and 6—or they set no limit at all.

Among the districts that do specify class size limits for middle grades, for example, most Virginia school districts allow up to 35 students per classroom in grades 4-6. Los Angeles Unified School District in California allows up to 41 students per classroom at the 6th-grade level (the highest limit in the sample). Florida school districts provide the lowest middle-grade ceiling, limiting class sizes to 22.

In the case of secondary classrooms, where most districts don’t have an explicit class size policy, Omaha Public Schools in Nebraska is notable. Middle school classrooms are capped at 16 students per classroom and high school classrooms capped at 20—substantially lower than the class sizes typically associated with secondary classes.

It is important to note that Florida districts, together with other districts around the country, have redefined the scope of once-strict class size policies, not only due to the extraordinarily high cost of lowering class sizes by even one student across a large district, but also the limited supply of teachers. That may explain why some Florida districts (and a few others) set class size limits on only “core curricula courses” for the secondary grades. The current legislative iteration of Florida’s early 2000s well-known attempt to shrink class sizes does not define “core,” creating a welcome loophole for those districts struggling to find teachers. In other districts, such as Albuquerque, or Chicago, class size limits are restricted to English classes, a nod perhaps to the higher workload experienced by English teachers.

Practical considerations

A violation of class size restrictions in the vast majority of districts does not appear to have real consequences—at least not ones set in stone. Fifty-four percent of the districts in our sample that have defined class size limit policies fail to mention any consequences if a school exceeds the class size limits. In a small percentage of cases (10%), the prescribed actions appear relatively benign, including a requirement to notify parents, requesting meetings with the principal, administrators notifying the superintendent, or the formation of an unspecified “committee”. Less than a third of districts with class size limit policies require measures that cost a district money, such as assigning a paraprofessional, increasing the teacher’s pay, or creating additional classes.

The lack of enforceability of class size policies could be a symptom of the impractical nature of implementing class size reduction policies across the board. Our colleague Marguerite Roza at the Edunomics Lab has written extensively about this issue, offering sound advice for districts.

What is striking about the many approaches districts take in this regard is the absence of efforts to reduce class sizes for economically disadvantaged students, where research has shown clear academic benefits, especially in the early grades. Only a few districts in our sample, such as Boston, New York City, St. Paul, Minneapolis, and Anne Arundel, have specified lower class size limits for high-poverty schools. These limits are usually one to three students per class lower than their standard class size limits. As school districts begin to spend down their ESSER funds, and assuming there are available teachers to hire, devoting a portion of funds to this kind of targeted class size reduction is very much in the spirit the funding was formulated, and would achieve a less congested learning environment, something both students and teachers would welcome.

More like this